Journal de Ciencias Sociales Año 13 Nº 25

ISSN 2362-194X

Education and healthcare of migrant children in a context of social mobility of parents in Hueyotlipan, Tlaxcala

Yean Flores1

Jose Dionicio Vázquez Vázquez 2

El Colegio de Tlaxcala, A.C.

Scientific Article

Material original autorizado para su primera publicación en el Journal de Ciencias Sociales, Revista Académica de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad de Palermo.

Received: 2024-03-05

Acceptance pending issue assignment: 2025-04-11

Abstract: This article analyzes social mobility of child population of some return migrant communities in Tlaxcala state, reflected through the level of access to public education and health services as indicators of socioeconomic development of their communities, also linked to the mobility capacities of their families under the influence of accumulated results derived from the migratory experience, and how the level of access to these services in the municipality of Hueyotlipan, Tlaxcala, affects returning migrant children from the United States. Regarding the main evidence, it was found that none of the returning migrant parents has been able to reuse their technical-labor knowledge or replicate their occupations that they had in the U.S., which is why, currently, they earmark up to more than half of their monthly income to education and healthcare services. However, they consider that they are in a better socio-economic situation and live in better households than those in which they lived when they were children, establishing that there is an upward social mobility. However, contextual differences between communities of arrival and return result in downward mobility in this families, both in terms of income, access to satisfaction and quality of life, coupled with a sense of discomfort in the process of arrival of children which impacts in their adjustment process to return communities and their academic development; thus, motivating the family to start a new migratory journey as their sole mechanism to achieve upward social mobility.

Keywords: return migration; social mobility; childhood; education.

Educación y salud de infantes migrantes en un contexto de movilidad social de los padres en Hueyotlipan, Tlaxcala

Resumen: El presente artículo analiza movilidad social de la población infantil de algunas comunidades migrantes de retorno del estado de Tlaxcala, reflejada a través de su nivel de acceso a servicios públicos de educación y de salud como un indicador de desarrollo socioeconómico de sus comunidades, vinculado a las capacidades de movilidad de sus familias bajo la influencia de resultados acumulados y derivados de la experiencia migratoria, y cómo afecta a los infantes migrantes de retorno provenientes de Estados Unidos, el nivel de acceso a dichos servicios en el municipio de Hueyotlipan, Tlaxcala. Respecto a las principales evidencias se encontró que ninguno de los padres migrantes de retorno ha podido reutilizar sus conocimientos técnico-laborales ni replicar sus ocupaciones que tenían en EE.UU., razón por la que, actualmente, destinan hasta más de la mitad de sus ingresos mensuales a educación y salud; sin embargo, consideran encontrarse en una mejor situación socioeconómica y vivir en hogares mejores que en los que vivían cuando eran niños, pudiendo establecer que existe una movilidad social ascendente. Empero, las diferencias contextuales entre comunidades de llegada y de retorno, devienen en una movilidad descendente en la unidad familiar, tanto en ingresos, acceso a satisfactores y calidad de vida; aunado a una sensación de malestar en el proceso de llegada de los infantes que complica su acoplamiento a las comunidades y su formación académica; motivando en la familia emprender un nuevo trayecto migratorio como único mecanismo de movilidad social ascendente.

Palabras clave: migración de retorno; movilidad social; infancia; educación.

1. Introduction

Over the last two centuries, binational relationship between Mexico and the United States of America (U.S.) has framed human displacements from one side of the border to the other. However, since the beginning of the 21st century, different security, economic and health global crises such those after 9-11 terrorist attack, real estate crisis of 2008 or the CoVid-19 pandemic in 2020, have led to changes in the direction and composition of migratory flows between the two countries. As a result, migrants head to the Mexican border after a migratory period in the U.S., resulting in the phenomenon of return migration.

This return is conducted both by the Mexican migrants who left their community of origin, and by those with whom they share blood and socio-affective bonds, such as spouses and, particularly, children. Said infants may have been born in Mexico and have migrated with their parents; yet, in most cases, they were born in the U.S., making them American citizens who arrive for the first time in Mexican communities, which differ to their birth context both in socioeconomic matters and in historical-cultural elements.

These contextual differences pose challenges to families of returning migrants: children must be integrated into a new environment where life rhythm must be learnt to fit into the community; and bureaucracy of Mexican institutions, due to their nationality and documentation, hinder their access to public services of education and healthcare. Meanwhile, parents face the challenge of reintegrating into local labor market with different wages and quality of employment to their prior occupations in the U.S., which jeopardize family income and access to social security for whole family unit.

As a result, contextual differences might lead to a decrease in the social mobility of these families, additionally determining development of the population in the return communities: at individual level, it will limit alternatives of social mobility of parents (in the present) and infants (in the future); and, at collective level, it will reduce local development alternatives of migrant communities due to the inability to leverage accumulated capital of Returning Migrant Families (RMF), depending on migration and remittances as the main mechanism of upward social mobility.

Hence, this research aimed to diagnose the condition of social mobility of the families of Returning Migrant Children (RMCH) from the U.S. in basic education through their access to education and healthcare services in Hueyotlipan, a municipality in the state of Tlaxcala, Mexico. It also proposed to describe the post-return use of both technical-labor knowledge of Returning Migrant Parents (RMP) accumulated in the U.S., and of household income to invest in educational training and disease treatment of RMCH; as well as to identify the effects on school performance of RMCH in their integration in Mexican educational services.

Preliminarily, it was found that RMCH experience adverse local and school adaptation processes, mainly those born in the U.S.; likewise, RMF experience downward social mobility with respect to their pre-return life, and the project of re-emigrating to the U.S. prevails, even if it requires family disintegration or to stop educational training of RMCH.

2. State of Art

Studies on return migration are relatively new (Carrillo Cantú & Román González, 2021), and although plans and programs to support return migrants have been contemplated in Mexico along the 21st century (Masferrer, 2021); a local approach has been urged as the number of returnees increases. As a result, studies on their living conditions, needs, and challenges have been directed towards the generation of policies and plans for the development of returnees and their communities (Betanzos, 2018).

Return migration studies have endorsed socioeconomic characterization of return (Larios, 2018) based on premises such as the number of returnees, their time-space context, reasons for migrating, use of accumulated capitals, among others. Likewise, studies on territorial effects of return have highlighted educational development as a pillar of population progress, pointing to promote public policies to guarantee educational mobility in rural return communities (Centro de Estudios Espinoza Yglesias [CEEY], 2019) on account of socioeconomic, curricular and cultural barriers to academic reintegration of returnees (Betanzos, 2018).

In Mexico, 68.9% of the return migrant population has an average schooling of 0 to 9 years, which is a lower educational preparation than that of the non-migrant population (Canales & Meza, 2018). Similarly, difficulties faced by return migrants are linked to the impossibility of reintegration into the labor market, preventing them from advancing in their occupational mobility, which would carry complications in their wealth mobility (Masferrer, 2021). Moreover, migration limits access to services such as housing, health, education, and employment, representing a challenge for returnees and an emerging object of study (Carrillo Cantú & Román González, 2021; Valdez et al., 2018); and, from the issues that reintegration generates, a question arises: why would migrants return to the precarious conditions they originally scaped from? (Canales & Meza, 2018).

3. Methodology

The municipality of Hueyotlipan, Tlaxcala, was selected for this study due to its prominent migrant tradition as noted by Vázquez (2017) which dates to the 1970s setting connections with Wyoming state in the U.S., throughout which a recognizable transnational network arises. Despite 300 households receive U.S. remittances, the municipality still faces significant socioeconomic challenges: 77% of its 15,000 residents live in poverty; 41% of its labor force are unemployed; its Gini coefficient of 0.34 is among the highest in Tlaxcala state; and its average education level is approximately eight years (Secretaría de Planeación y Finanzas [SPF], 2021; dataMéxico, 2022).

This work draws on ethnographic research by Guber (2011) and Restrepo (2016) to contextualize local knowledge and practices. Initially, the social mobility conditions of RMF were analyzed through secondary data from public institutions (SPF, 2021; dataMéxico, 2022), followed by an exploration of how returnees experience this phenomenon. Based on the typology of Canales & Meza (2018), participants were selected from households with transnational and binational children enrolled in institutions of Mexican basic education.

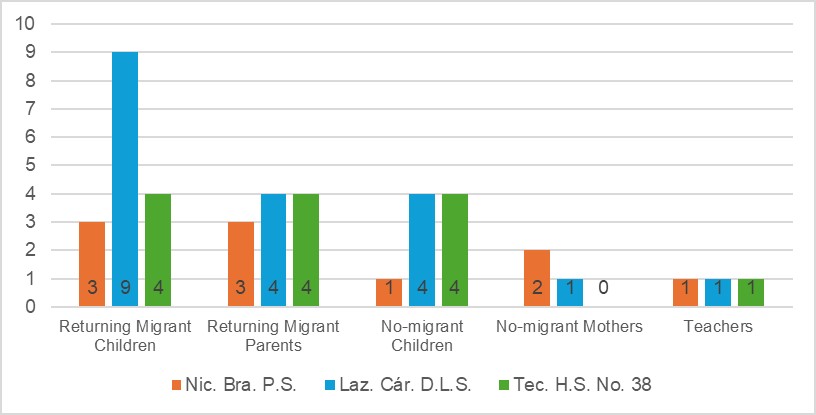

Subsequently, after an initial immersion with key informants from migration and public institutions in Hueyotlipan, a work-field calendar was designed with educational institutions that had migrant students between September and December 2022; semi-structured interviews supported by field diary were applied as the main tools of ethnographic research (Guber, 2011; Restrepo, 2016). For this purpose, five semi-structured interview instruments were designed for each type of participant (see Figure 1).

Interviews took place in three education institutions in Hueyotlipan: from San Simeón Xipetzinco locality, Nicolás Bravo Primary School and General Lázaro Cárdenas Distance-leaning School; and from San Idelfonso Hueyotlipan locality, Technical High School No. 38. There were 41 participants (see Figure 1): RMCH (16), RMP (11), No-migrant Children (NMCH) (9), No-migrant Mothers (NMM) (3) and teachers with returning migrant students (3).

Figure 1. Interview participants by group and school. Source: fieldwork, 2022.

Most participants (12) are from San Simeón Xipetzinco; the rest (4) are from San Idelfonso Hueyotlipan. All (16) are on morning school shift. Most are girls (10), and the rest are boys (6). They are basic education students in the last 2 grades of primary school: 5th (2) and 6th (1); and from the 3 grades of secondary school: 1st (1), 2nd (5) and 3rd (7). By age span, they are children between 11 and 14 years old. Analyzing their birthplace and age of return, they are mostly cases of Transgenerational return as mentioned by Zúñiga (2013) and Durand (2004), since almost all the interviewees (15) were born specifically in 3 states in the American Northwest: Montana (2), Utah (2), and Wyoming (9); however, 2 cases reported not remembering their place of birth in the U.S. To preserve interviewee’s identity and privacy, names displayed along results discussion are pseudonyms only referring sex of participants.

4. Theoretical Perspective

4.1. Return Migration

Frank Bovenkerk (1974, p. 5) defines return migration as "when people return after having migrated for the first time to their country or region of origin"; Gandini et al. (2015) add that it should be considered as such any movement in which individuals return to their place of origin regardless stay-length, returning reasons, etc.; since not doing so would deprive return migration of the vulnerability and risk under which it is sometimes carried out, and as it can be conditioned by economic achievement and socio-political forces on the migrant (Arroyo & Rodríguez, 2014).

Although return migration is not strictly conditioned by the temporality of the stay; stay-length, both abroad and in the community of origin, does have effects on the conditions and results of return (Bovenkerk, 1974), deriving in a diversity of phenomena on returnees, highlighting the construction of family bonds that derives in what Durand (2004) defines as transgenerational return, which involves both migrants and their offspring, implying the presence of blood and cultural bonds that influence local reintegration process.

RMCH are, therefore, part of this transgenerational return; yet it is important to distinguish between those born in Mexico and those born abroad due to the cultural and social divergences that form issues of post-return reintegration. First, transnational infants refer to those born in Mexico who migrated to the U.S. (Moctezuma-Longoria, 2013; Zúñiga, 2013); on the other hand, binational infants are those with two nationalities, having been born in the United States but being descendants of Mexicans.

Thus, while return entails multiple causes and periods (De La Sierra et al, 2016; Durand, 2004), its effects on individualsare diverse according to the conditions of return and the population group; additionally, migratory experiences of RMCH derives from sociodemographic features of their returning household and community contexts (Canales & Meza, 2018), making return a heterogeneous migratory displacement.

4.2. Components of Social Mobility

Social mobility is defined as changes in socioeconomic status experienced by individuals because of their rise or fall in economic, occupational, and educational scales; changes that fluctuate and depend on sex, ethnic-racial origin, family inheritance, replication of social capitals, and territorial socioeconomic characteristics (Serrano & Torche, 2010). In this regard, according to Sorokin (1961) and CEEY (2019), there are two types of displacement: horizontal mobility, understood as movement within the same social stratum without significant changes in social position; and vertical mobility, which implies an upward or downward transition between social strata with significant changes in the socioeconomic, occupational, and/or educational position of individuals.

This work works with 3 forms of social mobility: educational, occupational and wealth. The first is understood as opportunities for education within a society, ranging from education quality and years of training (CEEY, 2019); it is relevant in the socioeconomic development of nations due to its repercussions on occupations, income in the labor market, occupational stratification of society, level of innovation and technological development of regions; as well for the education factor in the relationship between social origin and social destiny in the so-called Social Mobility Triangleaccording to the human capital theory(Márques-Perales & Fachelli, 2021).

On the other hand, occupational mobility stands for the fulfilment of individuals in the labor market derived from their academic preparation that conditions and gives an approximation of income people could receive depending on their economic and work activities (CEEY, 2019). In studies of social mobility, attention has been drawn to this mobility because it is the central axis of the division of labor as the basis of social stratification and inequality (Yaschine, 2012), as well because of the importance of work as a means of achieving well-being derived from its retributions and remunerated resources.

Finally, wealth mobility involves the way in which families consciously employ or invest their capital to their offspring to access well-being satisfiers such as education and health services (CEEY, 2019) that also reflects the ability to face economic setbacks. Thus, the relationship between social class and wealth mobility is expressed in the ideas, priorities and modes of consumption (Sautu, 2020) that determine class structure and social stratification.

5. Results

5.1. Classroom Integration and Environment in the Returning Community

First, almost all RMCH were born in the U.S. and lived, pre-return, in their birth-state along their families; and, as latterly discussed, they lived in households that could be classified as Low-income (see Chart 4) based on their parents’ salary, yet they describe them as comfortable to live in. In addition, 11 arrived in Mexico being no more than 5 years old, a reason their parents did not enroll them in school in the U.S., which was later reflected in varied and complex post-return experiences.

To illustrate, neither 'Gabriel' and 'Isabel' assisted school in the U.S; still, both experiences are dissimilar: 'Isabel' arrived in San Simeon Xipetzinco —where she currently lives— being 6 months old, having no memories nor academic life in the U.S. However, 'Gabriel' arrived in Mexico being 3 years old; and, although he did not attend school in the U.S. either, he affirmed speaking English when he arrived in Mexico and expresses a current lack of understanding of Spanish as a reason that affects his academic experience.

Zúñiga & Carrillo Cantú (2020) state that RMCH experience difficulties in post-return school insertion since many of them, like 'Gabriel', have English as their first language and communication in Mexican is mainly conducted in Spanish, ignoring prior linguistic competencies of RMCH. In addition, Spanish skills RMCH learn at home are for basic communication not related to academic issues, limiting school communication and projecting shyness and submissiveness to their peers and teachers.

Furthermore, 'Daniela' experience stands out because of her pre and post return trajectory, her life story and, for the purposes of this section, her experience with Spanish language, linguistic register and the interferences between English and Spanish that could be perceived in the interview. 'Daniela' communicates with a Spanish proficiency level equivalent to A2-B1 according to Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR3 ) (Cambridge University [CU], n.d.); but the influence of her mother tongue, English, manifested in her pronunciation, sentence-building, idiomatic expressions and the pauses to mentally select the Spanish term required to communicate; being possible to affirm that her spoken communication is with Spanish-language vocabulary with English-grammar bases.

'Daniela', 'Gabriel' and 'Paty' experiences highlight their status as binational migrants as a factor related to their complex post-return school integration. Canales & Meza (2018) and Díaz Quintero and Sabillón Zelaya (2021) state that returnees are sometimes assigned a social stigma derived from their migratory experience and/or their type of return, especially if it was due to deportation. Herrera & Montoya Zavala (2019) say that RMCH’s nationality might cause school alienation as they are labeled as "the gringos" in the classroom.

'Daniela', 'Leonor' and 'Paty' reported challenges integrating into Mexican schools, as they notice differences in education and the pace compared to American school life. ‘Paty’ shared that, after a year, she gained confidence and made stronger connections with her classmates. Conversely, despite having lived in Mexico for about two years, ‘Daniela’ continues to struggle with classroom dynamics and peer bullying due to her Spanish-language abilities; moreover, ‘Teacher. Alberto’, her tutor, acknowledged her exceptional academic performance despite these difficulties. Worth mentioning that ‘Teacher. Carlos’, an English teacher at Technical High School No. 38, noted that RMCH face challenges adapting to daily life and school environment due to contextual differences between U.S. and Mexican societies.

Jacobo Suárez (2016) emphasizes the role of Spanish proficiency in RMCH leaning process, particularly in school subjects such as History and Literature for which a deeper textual understanding and reading comprehension is necessary; as well with problems with other subjects like Geography, History and Civic and Ethical Education due to differing sociocultural foundations built up by their U.S. upbringing (Zúñiga, 2013; Zúñiga & Carrillo Cantú, 2020; Carrillo Cantú & Román González, 2021).

This study found History (7 cases), Civic and Ethical Education (3 cases) and Spanish (2 cases) as particularly difficult subjects for RMCH, who also dedicated extra time to studying them. By contrast, NMCH reported struggles with Mathematics (5 cases) and Nature Sciences (4 cases), no attributing obstacles to Spanish-language comprehension, which is a significant issue for RMCH.

On the other hand, cases such as that reported by ‘Mrs. Inés’, mother to ‘María’, are examples of what Herrera & Montoya-Zavala (2019) and Zúñiga & Carrillo Cantú (2020) state about requirements of Mexican bureaucratic system over RMCH documentation. ‘María’, a U.S.-born student, was demanded at Technical High School No. 38 to present a Mexican birth certificate to keep studying, otherwise she would be dismissed. However, as ‘Mrs. Inés’ was an undocumented migrant in the U.S. when ‘María’ was born, it is difficult for them to get an American birth certificate —needed to Mexican birth certificate issuance— without a nationality-documentation agent in Mexico, which represents a high economic investment for their family, the reason why this process has extended. On the risk o ‘María’ being dropped out of school, ‘Mrs. Inés’ has argued with school principal so her daughter can continue her academical formative process in the institution.

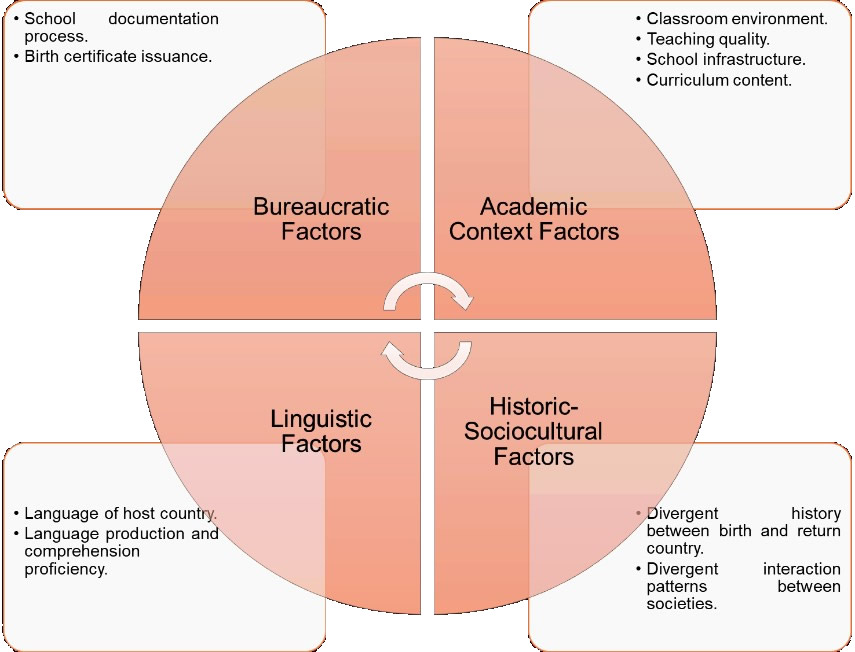

Based on experiences shared by RMCH and their parents, this research found four groups of factors of challenges and difficulties which complicate post-return integration of RMCH to Mexican communities and their institutions (see Figure 2). Bureaucratic Factors involve documentation Mexican institutions need from RMF to access or continue RMCH education, often creating segregation and hindering training, especially for those with dual nationality. Academic Context Factors include differences between Mexican and U.S. schools including curriculum, infrastructure, services, peer interaction and teacher quality, all of which influence RMCH performance and retention in Mexican education system and its institutions.

Historic-Sociocultural Factors (Figure 2) refer to challenges faced by RMCH, such as unfamiliarity with the host country’s historical and cultural foundations, values and social norms. Said factors affect their interaction with local and school communities, stigmatizing them as outsiders and devaluing cultural knowledge grasped from their birth country. Finally, Linguistic factors allude to the gap between local language, Spanish in this case, and the RMCH’s mother tongue, which affects daily communication, access to classroom learning and significantly impacts in their academic progress, social integration and the pace they adapt to the Mexican return communities’ norms and values.

Figure 2. Factors affecting school performance and local integration of Return Migration Children. Source: fieldwork, 2022.

‘Teacher Belén’ from Nicolás Bravo Primary School highlighted that local socioeconomic conditions and household precariousness not only prompt parents to consider remigrating to the U.S. but also causes school dropout and influence life projects of Hueyotlipan children, whether from migratory or non-migratory families, around the idea of migration or returning, in the case of U.S.-born children, to seek better living conditions and opportunities for self-development. Moreover, when asked about migrating to the U.S., 14 RMCH and all NMCH answered affirmatively, despite hesitation derived from family bonds in Hueyotlipan, agreeing on the belief that the U.S. offers superior job, income and living prospects for their future.

5.2. Returning migrant parents in the use of their technical-labor skills and social mobility

About labor occupations of RMP, it was considered, as point of reference, their first job upon their arrival in the U.S. and then, their last job prior to returning to Mexico. It was found that almost all the RMP arrived to work in hotels (4 cases) or restaurants (5 cases) in their host states, but almost all of them in Jackson County, Wyoming. Moreover, various experiences (3) rated the first jobs in the U.S. as "poorly paid, hard, and of poor quality”; and, although periods vary according to each RMP narrative, 9 reported improving their work conditions in a new job after no longer than two years in their initial one.

In the second work period questioned, prior to returning to Mexico, 5 RMP reported remaining in the same job and sector throughout their stay in the U.S. (hotel and restaurant). However, 6 cases are relevant because half of them show upward occupational mobility processes throughout their stay in the U.S., and the rest showed labor inactivity for child-upbringing with sporadic middle-paid jobs, exclusively in the case of returning migrant mothers.

Income of RMPs in the U.S. varied according to their occupations, number of jobs, length of workday, and form of payment (hourly, daily, weekly, etc.); thus, an income analysis is established based on a weekly scheme considering that 8 of the RMP reported receiving income per hour, 1 per week, 1 per house cleaned and 1 per biweekly salary. Therefore, and to simplify this interpretation and analysis of results, a weekly wage and income scheme was set up considering an 8-hour day for 5 days a week4 (see Chart 1).

Chart 1. Weekly Income in Last U.S. and Current Mexican Employment

Returning Migrant Parent |

Last employment in the U.S. |

Current employment in Mexico |

Mrs. Adriana |

500 USD (9695.00 MXN) |

NP |

Mrs. Berenice |

2, 650 USD (51, 383.50 MXN) |

750 MXN |

Mrs. Clara |

260 USD (5, 041.40 MXN) |

240 MXN |

Mr. Domingo |

720 USD (13, 960.80 MXN) |

3, 000 MXN |

Mrs. Eréndira |

300 USD (5, 817.00 MXN) |

NP |

Mrs. Fatima |

150 USD (2,908.50 MXN) |

NP |

Mrs. Gladys |

700 USD (13, 573.00 MXN) |

600 MXN |

Mrs. Heidi |

520 USD (10, 082.80 MXN) |

NP |

Mrs. Inés |

400 USD (7, 756.00 MNXN) |

900 MXN |

Mr. José |

1,120 USD (21, 716.80 MXN) |

1, 000 MXN |

Mrs. Karla |

NS |

NP |

|

NS: Not-specified income |

NP: No payment |

Source: Fieldwork, 2022.

However, unlike ‘Mrs. Eréndira’, the economic remuneration of most of the interviewees was not complemented by any type of social security or health insurance provided by their employers. On the other hand, and based on the results obtained regarding post-return labor occupations in Mexico, it was found that none of the RMP perform in any economic activity similar or related to the one they had in the United States (see Chart 2), not being able to apply, in their current functions, knowledge and skills accumulated abroad.

.

Chart 2. Pre- and Post-Return Occupations of Returning Migrant Parents

|

Occupation |

Returning Migrant Parent |

In the U.S. |

In Mexico |

Mrs. Adriana |

House Cleaning |

Housewife |

Mrs. Berenice |

Cashier |

Domestic worker (House Cleaning) |

Mrs. Clara |

Hospitality & Cleaning |

Artisan |

Mr. Domingo |

Hospitality & Cleaning |

Farmer |

Mrs. Eréndira |

Babysitting |

Housewife |

Mrs. Fatima |

Babysitting |

Housewife |

Mrs. Gladys |

Hospitality & Cleaning |

Store Clerk |

Mrs. Heidi |

Hospitality & Cleaning |

Housewife |

Mrs. Inés |

Babysitting |

Cattle breeding |

Mr. José |

Building Sector |

Farmer |

Mrs. Karla |

Hospitality & Cleaning |

Housewife |

Source: Fieldwork, 2022.

On the other hand, while one case referred to having used migration savings to open a small business; the rest of the RMP (10) used their saving for post-return household and familiar maintenance, and not for starting a familiar business. About it, Arroyo and Rodríguez (2014) establish that the relationship between remittances and business entrepreneurship in post-return communities is low or almost non-existent. In addition, ‘Mrs. Berenice’ says that she did not currently work because family expenses are covered by remittances sent by her husband in the U.S., who decided to remigrate due to the lack of job opportunities in the community of return.

This analysis focuses exclusively on the occupational activities and income of the interviewed RMP to examine changes in social class and income level resulting from their occupational pre and post return shift. It also explores how RMP’s social mobility, as heads of returnee families, influences overall family mobility, given their individual wage and labor determine RMCH’s educational and wealth mobility (CEEY, 2019). Although other family members’ earnings may compensate to household support, that would evidence a lack of financial liquidity in the RMP’s income, which is a trend in a significant amount of returnee households due to a discrepancy between income and expenses (Meza & Pederzini, 2009; Urriza, 2017) which is commonly balanced out by remittances sent from the U.S.; yet it remarks high dependence on said economic resource to sustain life in return community.

Hence, the following results were found (see Chart 1): all parents experienced a decrease in their income level, where economic remuneration in their current activities is a fraction of what they previously earned. During their stay in the U.S., most interviewees (9) reported income that placed them in the lowest level of social class among American households according to Pew Research Center (Benett et al., 2023) which sets 3 social classes by income level: high, middle, and low, the latter being in which RMP were found pre-returning (see Chart 3).

Although low-income class prevailed among pre-return families; those in this class yearly earned fewer than 48,500 USD (Benett et al., 2023) which, as 3 RMP reported, was ‘more than enough’ to cover family expenses in the U.S.; allowing them to access developmental satisfiers such as educational, health, and housing services, especially for 2 RMP in the middle class who earned above 48,500 USD per year (see Chart 3).

Upon returning to Hueyotlipan, most RMP experienced a decline in wealth mobility (see Charts 1 and 3) according to criteria by Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social [CONEVAL] (2020). While ‘Mrs. Berenice’ and ‘Mr. José’ maintained their social class, six RMP lived in extreme poverty as mothers dedicated to unpaid household and childcare responsibilities, relying economically on relatives such as spouses or parents, or, in ‘Mrs. Adriana’s’ case, on remittances sent from the U.S. by a relative. Only ‘Mr. Domingo’ gained upward social mobility as his current income places him in the middle-class stratum.

CONEVAL (2020) stratifies Mexican socioeconomic classes based on economic income and access to satisfiers essential for social development such as education and health services, social welfare, housing and feeding. While migration, remittances and savings strengthen post-return economy of RMF with better housing and feeding compared to non-migrant families, as shown in other studies (Urriza, 2017; Betanzos, 2018; Larios, 2018), it is found that living abroad complicates access to the other essential services —something to deepen on section 5.3. Thus, RMF remain classified as vulnerable and extreme poverty population per CONEVAL criteria (see Chart 3).

Chart 3. Social Class by Income Level of Returning Migrant Parents

|

Social Class by Income Level |

Returning Migrant Parent |

in the U.S. |

In Mexico |

Mrs. Adriana |

Low |

Extreme Poverty |

Mrs. Berenice |

Middle |

Vulnerable |

Mrs. Clara |

Low |

Extreme Poverty |

Mr. Domingo |

Low |

Middle |

Mrs. Eréndira |

Low |

Extreme Poverty |

Mrs. Fatima |

Low |

Extreme Poverty |

Mrs. Gladys |

Low |

Medium Poverty |

Mrs. Heidi |

Low |

Extreme Poverty |

Mrs. Inés |

Low |

Vulnerable |

Mr. José |

Middle |

Vulnerable |

Mrs. Karla |

Not Specified |

Extreme Poverty |

Source: Authors' own elaboration with data from CONEVAL (2020), Benett et al. (2020), INEGI (2021) and World Bank [WB] (2022).

Moreover, literature reports that, upon returning to Mexico, returnees register a tendency towards salaried employment5 in their work occupations, which was confirmed with 3 RMP (‘Messrs. Domingo & José’ and ‘Mrs. Gladys’) who work as day laborers on farms or as clerks on business that is not their own nor was started from their remittances savings.

Based discussion so far, it can be assumed that, upon the return to Mexico, most RMF experienced downward social mobility, both occupational and wealth, based on their individual income. Nonetheless, in the next section it will be pointed out that migratory experience did allow RMF to build up more equipped houses with better services in their return communities in Hueyotlipan —due to remittances and post-return savings, matching upward wealth mobility; however, it will also be noticed that said economic resources do not last long after returning; and, as soon as they are depleted, downward social mobility is experienced along a lack of access to public educational and health services, compromising occupational, wealth and educational mobility of RMF.

5.3. Use of Family Income in Health, Education, and Housing Services for the Development of Returning Migrant Children

Most RMF in Hueyotlipan live in two-story houses with basic services (electricity, water, gas and telephone) which they own and that is a quality that makes them better than their previous rented properties in the U.S., according to RMP, as a significant portion of their income there went to high-cost housing, despite the better infrastructure and services available abroad. However, ‘Mrs. Berenice’ and ‘Mrs. Clara’ live in houses borrowed from relatives: ‘Mrs. Berenice’ relocated to a cheaper area in San Simeón Xipetzinco; and ‘Mrs. Clara’ lacks a property of her own. On homeownership, only one No-Migrant Mother (NMM) reported owning a house of her own which was inherited from a relative, while all NMM referred not to earn enough to buy property to live in.

Furthermore, analyzing RMP social mobility based on household quality when they were children to their current one, it was found that all RMP rate their present home as better. In their childhood homes, there was a shortage of services such as potable water in 3 cases, electricity in 2 and natural gas for cooking in 4; likewise, half of them lacked firm floor (5 cases) and paved streets (7). Also, 4 RMP affirmed that access to basic educational services was a significant investment for their family economy.

These precarious economic conditions during RMP childhood were the main reason 8 of them did not complete basic education. Additionally, 'Mrs. Berenice' and 'Mr. Domingo' shared that they withdrew their academic formation because they migrated to the U.S. to begin their working life, truncating their educational training which supports Meza & Pederzini (2009) statement about the prioritization of migration as a source of familiar income over early childhood education investment.

Unlike their childhood conditions, current RMP households in their return community show upward mobility, with access to all basic services, adding telephone and internet, and seven RMP owning a car. Migration has clearly improved their economic conditions, leading to better living standards, which ten RMP recognized as positive changes. Conversely, NMM households reported minimal improvement, describing their conditions as a constant ‘humble yet sufficient’. These findings help affirm that migration can promote upward social mobility and positively affect living conditions in origin-return communities of migrants.

Additionally, significant differences arise between pre-return, in the U.S., and post-return, in Hueyotlipan, living conditions: abroad, all RMP had telephone, electricity and internet services and even their own car, while their current living conditions reflect downward social mobility. These disparities extend to access to healthcare services: in the U.S., 10 RMP lacked health insurance tied to their jobs, with only ‘Mrs. Adriana’ receiving medical support from her employer. Post-return, the situation stays limited, as only ‘Mrs. Berenice’ is insured by Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS), highlighting continued challenges in securing healthcare access.

On the matter, RMP were asked whether their children needed ongoing or periodical medical care. Four reported health conditions in their children: ‘Mrs. Adriana’ noted one child with ADHD; ‘Mrs. Berenice’ reported her daughter ‘Daniela’ with an electrical brain abnormality and her eldest son with autism; ‘Mrs. Eréndira’ mentioned a child with autism; and Mses. ‘Clara’ & ‘Heidi’ stated that their children live with asthma. Additionally, while 7 RMP reported no illnesses, they shared information about seeking medical care for family health needs.

When addressing their children's medical conditions, RMP responses varied. ‘Mrs. Berenice’, insured through IMSS, reported seeking psychological and psychiatric consultations for her children, Daniela’ and her older brother, though the lack of doctors, appointments, and medication represented challenges, particularly affecting her household income. In contrast, Mses. ‘Adriana’ and ‘Eréndira’, without health insurance, sought care for their children's ADHD and autism at the Comprehensive Rehabilitation Center (CRC) managed by Secretaría de Salud (SESA) in Apizaco, Tlaxcala, 22 km from their community in San Simeón Xipetzinco, Hueyotlipan. While ‘Mrs. Adriana’ acknowledged the CRC’s positive impact on her son's academic development and quality of life, she stopped treatment due to rising costs of medical services and medications.

It should be noted that 'Mrs. Adriana' depends entirely on remittances sent from the U.S. by her husband. In addition, 'Mrs. Eréndira' used CRC services to treat autism on one of her daughters born in the U.S.; however, at the time of the interview, she said that CRC Apizaco stopped operations due to CoVid-19 pandemic, having to rely on other minimally effective treatments. Although only 4 RMP reported child illnesses, the data for the other 7 reflect expenses for illnesses experienced since their return to the community.

This research aimed to document family income used for medical and educational services supporting RMCH development. Chart 4 shows health care expenses by RMP: 10 rely solely on private medical services, while 1, ‘Mrs. Berenice’, combines them with other options, with costs ranging from 200 to 27,000 MXN. Most expenses are non-recurrent; for instance, ‘Mrs. Gladys’ reported costs for a gastrointestinal procedure her U.S.-born daughter underwent upon returning to Mexico, covering procedures, medications and consultations. Similarly, sporadic medical appointments involve private sector expenses only during significant health issues, including consultations and medications.

In contrast, Mses. ‘Berenice’, ‘Clara’ and ‘Heidi’ reported regular expenditures of this type: ‘Clara’ and ‘Heidi’ per month, and ‘Mrs. Berenice’ twice a month. For the latest, such expenses requires almost her entire monthly income, while for ‘Mrs. Clara’ requires almost double of her income. For ‘Mrs. Heidi’, a housewife with no remuneration, these costs are covered by financial support from her relatives. Likewise, ‘Mrs. Karla’, who requires sporadic medical consultation when her children need it, highlights that these expenditures are significantly high and require borrowing funds.

Chart 4. Costs in Illnesses and Illnesses of Children of Migrant Parents

Returning Migrant Parent |

Illness or illness of the child |

Approximate cost of medical service per appointment |

Mrs. Adriana |

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) |

200 MXN |

Mrs. Berenice |

Brain electrical abnormality |

1, 300 MXN |

Mrs. Clara |

Asthma |

1, 200 MXN |

Mr. Domingo |

Sporadic medical appointment |

500 MXN |

Mrs. Eréndira |

Autism |

Not specified |

Mrs. Fatima |

Sporadic medical appointment |

400 MXN |

Mrs. Gladys |

Sporadic medical appointment |

27, 000 MXN |

Mrs. Heidi |

Asthma |

600 MXN |

Mrs. Inés |

Sporadic medical appointment |

Not specified |

Mr. José |

Sporadic medical appointment |

1, 500 MXN |

Mrs. Karla |

Sporadic medical appointment |

2, 000 MXN |

Source: Fieldwork 2022.

An analogous situation arises in access to public education services (see Chart 5). ‘Mrs. Berenice’ chose private education for her children as she and her husband it would closely resemble service quality of American academic institutions. However, financial constraints complemented with the beginning of CoVid-19 pandemic, which required investment in computers and internet service, led her to continue her children’s education in San Simeón Xipetzinco: her daughter was enrolled in Lázaro Cárdenas Distance-Learning School, and her son in Colegio de Bachilleres Public School No. 5. ‘Mrs. Berenice’ remarked differences between American and Mexican education systems: while the former required minimal financial investment, with a one-time fee of 300 USD, covering registration, supplies and all necessary services and materials; the later constantly demands fees, tuition and economic contributions despite being public and free educational system.

‘Mrs. Clara’, ‘Mrs. Eréndira’, ‘Mrs. Heidi’, and ‘Mr. José’ agreed that American public education demanded minimal economic investment (see Chart 5). ‘Mrs. Fatima’ adds that "it was expensive, yet affordable” as she did not pay for fees or registrations, and school supplies were paid only once in U.S. schools, usually at the beginning of school year and if anything was additionally required, the institution covered the expenses, a statement supported by 'Mrs. Berenice' and 'Mr. José'. Besides, three RMP reported not having spent much on fees or supplies in the U.S. for their children's education; however, they did not specify amounts. To that, NMM agreed that Mexican public education system requires frequent economic support from school parent community.

Chart 5. Returning Migration Parents Expenditures on Education for Returning Migrant Children

|

In the U.S. |

In Mexico |

|

School Fees |

School supplies |

School Fees |

School supplies |

Mrs. Adriana |

NSU |

NSU |

NS |

1, 500 MXN |

Mrs. Berenice |

1,000 USD monthly |

300 USD yearly |

800 MXN yearly |

800 MXN monthly |

Mrs. Clara |

1,500 USD yearly |

NS |

150 MXN yearly |

200 MXN monthly |

Mr. Domingo |

NSU |

NSU |

35 MXN daily |

1, 000 MXN yearly |

Mrs. Eréndira |

None |

150 USD yearly |

2,000 MXN yearly |

500 MXN monthly |

Mrs. Fatima |

NS |

NS |

1, 500 MXN weekly |

1, 000 MXN yearly |

Mrs. Gladys |

NSU |

NSU |

300 MXN weekly |

600 MXN monthly |

Mrs. Heidi |

NS |

100 USD yearly |

900 MXN monthly |

550 MXN monthly |

Mrs. Inés |

NSU |

NSU |

300 MXN weekly |

NS |

Mr. José |

NS |

NS |

2,000 MXN yearly |

1, 000 MXN yearly |

Mrs. Karla |

NSU |

NSU |

2,000 MXN yearly |

1, 000 MXN yearly |

|

NS: Not specified amount |

|

|

|

NSU: Children did not attend school in the U.S. |

Source: Fieldwork 2022.

The experiences of the five RMP whose children attended school in the U.S. converge in preference for the U.S. education system over the Mexican one based on its lower costs, superior infrastructure, teaching quality, individualized student monitoring and counseling, along with better school socialization environment. These valorization differences remark contextual disparities between destination regions in the U.S. and return regions in Mexico as said educational differences, alongside other previously named factors contribute to challenging reintegration processes for returnees within Mexican communities and schools. For the five RMP, school life in Mexico demands substantial investment, including enrollment fees, uniforms and supplies; something agreed by RMP whose children did not attend to U.S. schools and NMM, despite lacking direct comparison with U.S. educational costs.

Although school costs and fees vary from data shared by parents, a closer look at these expenses (see Chart 5) evidence a constant referred likewise by Mses. 'Eréndira', 'Fatima', 'Karla' and 'Mr. José': there is a substantial expenditure at the beginning of school year that corresponds to registration and school uniforms, and a continuous outlay covering supplies (see Chart 6) made weekly or monthly. In addition, these average costs are for each child, so a higher expense can be intuited in 8 RMP with several children currently studying, something confirmed by Mses. 'Adriana', 'Berenice', 'Fatima' and Messrs. 'Domingo' and 'José'; similarly, all NMM confirmed this finding, since all have more than one child studying.

Chart 6. Average School Fees and Costs Referred by Return Migrant Parents

Educational Institution |

Fees at the beginning of the school year |

School supplies |

School Uniforms |

Nicolás Bravo Primary School, San Simeón Xipetzinco |

1, 500 MXN |

500 – 1, 000 MXN |

NS |

Technical High School No. 38, San Idelfonso Hueyotlipan |

1, 500 MXN |

1, 000 MXN |

1, 000 MXN |

General Lázaro Cárdenas Distance-learning School, San Simeón Xipetzinco |

400 MXN |

800 – 1, 500 MXN |

NS |

|

NS: Not specified |

Source: Fieldwork 2022.

The experiences of Mses. ‘Berenice’, ‘Clara’ and ‘Gladys’ are cases where expenses on medical and educational services exceed half of their monthly income, a situation largely influenced by the health conditions on two of their children. Conversely, while ‘Mrs. Inés’ and ‘Mr. José’, the RMP with the highest monthly income, seemingly face no difficulties covering school fees and supplies —particularly as their children do not require constant medical attention—all families reported a decline in their financial situation since returning to their current community as remittances and remittances run out from their economic stock. They perceive their household incomes as insufficient to provide their children with a standard of living like what they had back in the U.S.; as a result, 7 RMP consider remigrate to the U.S. to support family expenses.

Preliminarily, it was found RMP consider to be in a higher socioeconomic level to that they were in during childhood (upward mobility); yet, simultaneously, they report a lower socioeconomic level to that they were in the U.S. (downward mobility), and consider that, given the structural conditions of their current community in Hueyotlipan, Tlaxcala, the best option for their children's development is migrating to the U.S., finish their academic training and take advantage of job opportunities available in that country. According to the RMP, migrating will be easier for their children, RMCH, because of their double nationality.

Moreover, although RMP value educational training of their children as a means for a better life quality, social progress and better employment and income opportunities; they recognize, simultaneously, that such attributes would be sterile in environments with adverse socioeconomic conditions, such as in their current communities in Mexico, where such talents, skills and knowledge would not germinate, needing to relocate geographically to environments where those attributes can be well exploited, such as those they were able to take advantage of in the U.S.

6. Conclusions and recommendations

An analysis of RMCH’s narratives, compared to RMP’s socioeconomic trajectories, shows that financial capital accumulated through migration offers RMF precariousness containment and helps upward social mobility. However, this condition is temporary as, over time, financial standing of RMF becomes nearly indistinguishable from that of non-migrant families, and all knowledge and skills acquired in their previous jobs in the U.S. cannot be replicated under local-structural conditions. As a result, families distribute most of their resources to attend health needs and ensuring educational opportunities for their children, which limits the lasting impact of migrant-earned capital.

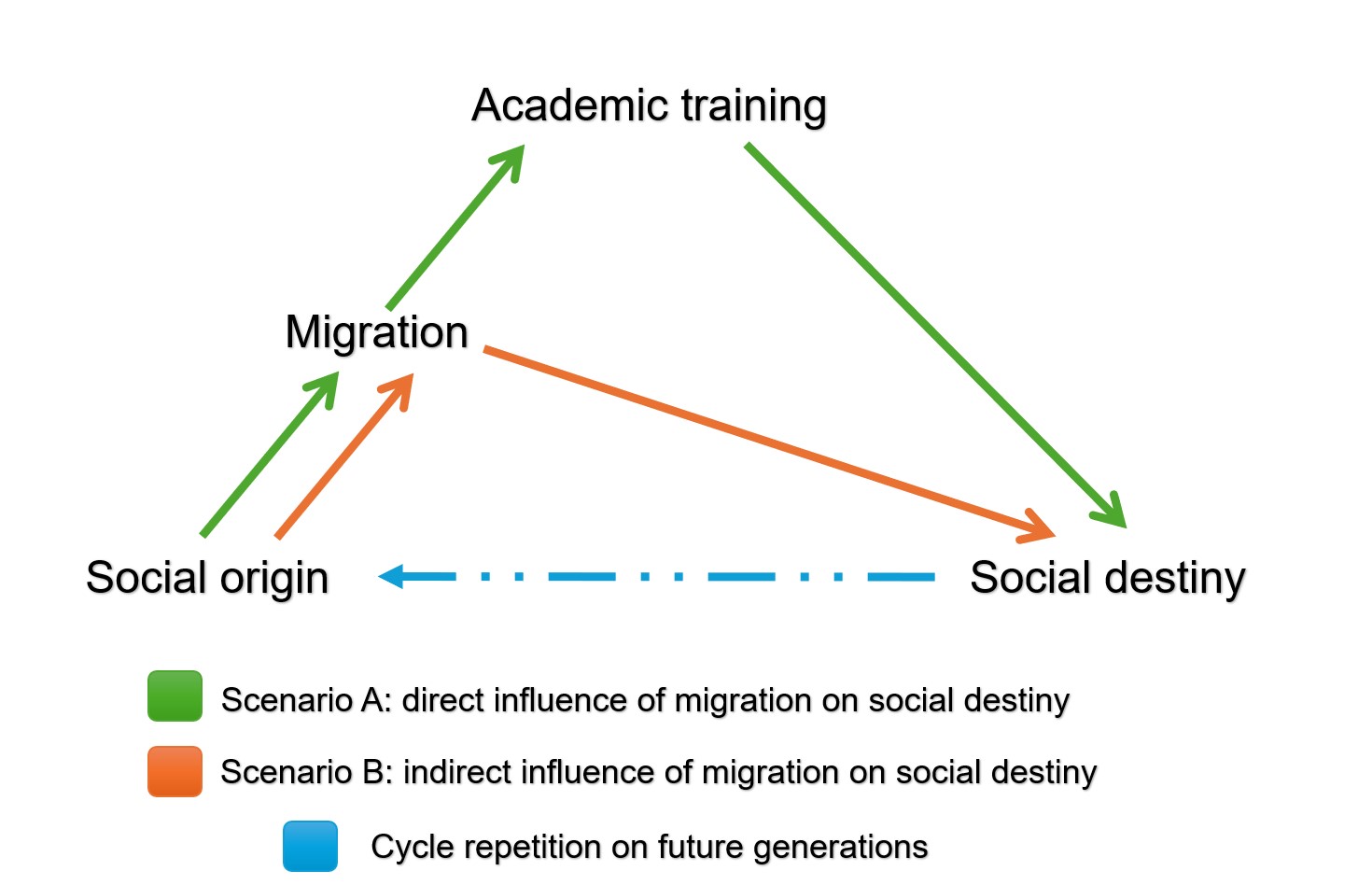

Likewise, it is possible to sketch a panorama of the alternatives of social mobility that communities with migratory experience throughout Mexico, as Hueyotlipan, and their population will have in the future. According to Márques-Perales & Fachelli (2021), social origin conditioning social mobility destiny might be modified with educational mobility through higher education as it impacts on their occupational and wealth mobility; nonetheless, findings in this research tend to align more with Meza & Pederzini (2009) and Zúñiga & Carrillo Cantú (2020) about higher education being disrupted by migration due to contextual socioeconomic conditions of migrant communities and migrant families’ project.

RMP shared the wish for their children, RMCH, to finish their academical training to get better living conditions to those they had; yet they recognize it might be better used in the U.S. on behalf of its social and economic conditions. Therefore, this research proposes a Social Mobility Triangle, as that discussed by Márques-Perales & Fachelli (2021), that integrates migration as a modifier of social destiny (Figure 3) and two possible case scenarios.

Figure 3. Triangle of Social Mobility with Migration as a Modifier of Social Destiny.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on Márques-Perales & Fachelli (2021).

Scenario A in Figure 3 depicts the direct impact of migration on social mobility, where RMCH migrate to foreign labor markets, often disrupting their education. This may lead them to nobs with similar wages as their parents, perpetuating the cycle across generations. Oppositely, scenario B reflects ideas of Márques-Perales & Fachelli (2021), as well as RMP’s aspirations and RMCH’s projects. Here, migration influences social destiny indirectly: instead of working abroad, they leverage their dual citizenship to complete their education, potentially accessing diverse occupations with better conditions. This not only enhances their social mobility, but also helps their families and communities in Hueyotlipan.

Conclusively, it is necessary to redirect efforts and plans to Regional Development not only in the migratory communities of Hueyotlipan, but in all territories where migration is the main alternative for social ascent to reduce dependence on foreign markets and the fragility of local productive structures, strengthening and creating new synergies based on capitals that returnees arrive to their communities with. And most importantly, it is crucial to address Return Migrating Children’s needs, dreams and goals as it guarantees both inclusion —a vital component for any Regional Development project— and a society with opportunities not determined by social origin, with equality and justice for all.

Bibliographic references

Arroyo A. & Rodríguez, D. (2014). Migración y desarrollo regional, Movilidad poblacional interna y a Estados Unidos en la dinámica urbana de México. Universidad de Guadalajara, México.

Betanzos, I. (2018). Study of the Migratory Return: Analysis to the Condition of the Returned Migrant in the Educations and Labor Reintegration ant the Entrepreneurship as an Area of Opportunity. European Scientific Journal, 14(10), 83-98. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2018.v14n10p83

Bovenkerk, F. (1974). The Sociology of Return Migration: A Bibliographic Essay. Martinus Nijhoff.

Canales, A. & Meza, S. (2018). Tendencias y patrones de la migración de retorno. Migración y Desarrollo, 16(30), 123-155. https://doi.org/10.35533/myd.1630.aic.sm

Carrillo Cantú, E. & Román González, B. (2021). De Reversa y llegando por primera Vez a México. Rasgos sociodemográficos de Infantes y Adolescentes que migran de Estados Unidos a México. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 36(1), 193-223. https://doi.org/10.24201/edu.v36i1.1827

De la Sierra, L., González, M., Martínez, Y., & Cruz, J. (2016). La Salud como Motivo de Retorno de Migrantes a México. Nuevas Experiencias de la Migración de Retorno, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro de Investigaciones sobre América del Norte, México, 119-134.

Díaz Quintero, D. & Sabillón Zelaya, D. (2021). La migración de retorno y la inserción integral al contexto escolar y comunitario: propuesta de una política a beneficio de la niñez y adolescencia–familias migrantes en Honduras. Conocimiento Educativo, 8, 75-93. https://doi.org/10.5377/ce.v8i1.12591

Durand, J. (2004). Ensayo teórico sobre la migración de retorno. El principio del rendimiento decreciente. Cuadernos Geográficos, 35(2), 103-116. https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/cuadgeo/article/view/1784

Gandini, L., Lozano-Ascencio, F., & Gaspar, S. (2015). El retorno en el nuevo escenario de la migración entre México y Estados Unidos. Consejo Nacional de Población.

Guber, R. (2011). La etnografía: método, campo y reflexividad. Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

Herrera, M., & Montoya Zavala, E. (2019). Child migrants returning to Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico. A familial, educational, and binational challenge. ÁNFORA, 26(46), 137–162. https://doi.org/10.30854/anf.v26.n46.2019.557

Jacobo Suárez, M. (2016). Migración de retorno y políticas de reintegración al sistema educativo mexicano. In C. Heredia Zubieta (Coord.), El sistema migratorio mesoamericano (pp. 125-246). Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas.

Larios, A. (2018). La migración de retorno y las teorías con un enfoque hacia el desarrollo, descubriendo elementos para la construcción de la política pública desde lo local. In S. De la Vega y C. Rodríguez (Eds.), Condiciones Sociales, Empobrecimiento y Dinámicas Reginales de Mercados Laborales (pp. 625-643, Vol. 4). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Márques-Perales, I. y Fachelli, S. (2021). El impacto de la educación superior en la clase social: una aproximación desde el origen social. Revista de Educación y Derecho, (23). https://doi.org/10.1344/REYD2021.23.34435

Masferrer, C. (2021). Atlas de migración de retorno de Estados Unidos a México. El Colegio de México.

Meza, L. & Pederzini, C. (2009). Migración internacional y escolaridad como medios alternativos de movilidad social: el caso de México. Estudios Económicos, 27(107), 163-206.

Moctezuma-Longoria, M. (2013). Retorno de migrantes a México. Su reformulación conceptual. Papeles de Población, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, 19(77), 49-160. https://rppoblacion.uaemex.mx/article/view/8385

Restrepo, E. (2016). Etnografía: alcances, técnicas y éticas. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Serrano, J. & Torche, F. (2010). Introducción. In J. Serrano & F. Torche (Ed.), Movilidad Social en México, Población, Desarrollo y Crecimiento (pp. 7-22). Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesias.

Sautu, R. (2020). Clases sociales en el curso de la vida. In R. Sautu, P. Boniolo, P. Dalle & R. Elbert (Eds.), El análisis de clases sociales: pensando la movilidad social, la residencia, los lazos sociales, la identidad y la agencia (pp. 39-51, Vol. 1). Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani.

Sorokin, P. (1961). Estratificación y Movilidad Social, Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales de la Universidad Nacional.

Urriza, C. (2017). Calidad del Empleo y la Vivienda de los Emigrantes mexicanos retornados de Estados Unidos en 1997 y 2010 [Dissertation, Universidad Computense de Madrid]. Universidad Computense de Madrid.

Valdez, G., Ruiz, L., Rivera, O. y Antonio, R. (2018). Menores migrantes de retorno: problemática académica y proceso administrativo en el sistema escolar sonorense. Región y Sociedad, 30(72). https://doi.org/10.22198/rys.2018.72.a904

Yaschine, I. (2012). ¿Oportunidades? Movilidad social intergeneracional e impacto en México [Dissertation, El Colegio de México]. Repositorio Institucional - El Colegio de México.

Zamora, R. & Del Valle, R. (2016). Migración de Retorno y Alternativas de Reinserción: hacia una Política Integral del Desarrollo. Migración y Desarrollo Humano, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, Zacatecas, 1-14.

Zúñiga, V. (2013). Migrantes internacionales en las escuelas mexicanas: desafíos actuales y futuros de política educativa. Revista Electrónica Sinéctica, (40). https://sinectica.iteso.mx/index.php/SINECTICA/article/view/50

Zúñiga, V. & Carrillo Cantú, E. (2020). Migración y exclusión escolar: truncamiento de la educación básica en menores migrantes de Estados Unidos a México. Estudios Sociológicos, 38(114), 655-688. https://doi.org/10.24201/es.2020v38n114.1907

Other documents consulted

Cambridge University Press & Assessment (2023). International Language Standards. https://www.cambridgeenglish.org/exams-and-tests/cefr/

Banco Mundial [BM] (February 12, 2023). Ajuste en las líneas mundiales de pobreza. Información Básica. https://n9.cl/4tioc

Benett, J., Fry, R., & Kochhar, R. (July 23, 2023). Are you in the middle class? Find out with our income calculator. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/07/23/are-you-in-the-american-middle-class/

Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesias [CEEY]. (2019). Informe de Movilidad Social 2019, Hacia la igualdad regional de oportunidades. Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesias.

DataMéxico (August 29th, 2022). Hueyotlipan, Municipio de Tlaxcala. Hueyotlipan. https://www.economia.gob.mx/datamexico/es/profile/geo/hueyotlipan

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI] (2021). Cuantificando la Clase Media en México 2010-2020. Dirección General Adjunta de Investigación, México.

Secretaría de Planeación y Finanzas [SPF] (2021). Agenda Estadística 2021. Gobierno del Estado de Tlaxcala.

World Bank [WB] (February 12th, 2022). Fact Sheet: An Adjustment to Global Poverty Lines. World Bank: Factsheet.https://n9.cl/4tioc

.

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional.

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional.