Journal de Ciencias Sociales Año 8 N° 15

ISSN 2362-194X

Children’s Human Capabilities and Child Maltreatment: A Pilot Study of one

Secondary School in Aruba

Clementia Eugene1

University of Aruba

Tobi L. G. Graafsma2

University of Suriname

Scientific article

Original material authorized for its first publication in the Journal of Social Sciences, the Academic Journal of the Social Sciences School of Universidad de Palermo.

Reception: 16-10-2019

Approval: 23-07-2020

Abstract: There are no known studies that have explored a conceptual basis for valorizing child maltreatment as a human development impediment using the Human Capability Approach. The pilot study assessed the prevalence of child maltreatment amongst 68 (N=219) school-aged children 12 – 17 years in one secondary school in Aruba using Nussbaum’s list of 10 central human capabilities. Among this sample, the prevalence of child maltreatment was at 100%. The most prevalent types of child maltreatment were emotional abuse (94.2%), physical abuse (88.4%), severe physical abuse (66.7%) and neglect (42%). Sexual abuse had the lowest prevalence rate at 18.8%. The levels of functionings achieved varied according to types of child maltreatment and their prevalence. Neglect, witnessing inter-parental violence and sexual abuse were associated with lower achievements on the combined 10 central human capabilities except for emotional abuse, physical abuse and severe physical abuse which reported highest prevalence. These types of child maltreatment were too common and left little to no variability to calculate statistical relationships with the 10 human capabilities. These findings are disturbing and raise concerns about the normalization of abuse. Further research is recommended to determine the contributing factors to widespread use of emotional and physical abuse and the potential for intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment. Future research is also recommended with a larger sample that may provide more meaningful analysis of the capability space of children affected by child maltreatment.

Keywords: Child maltreatment; prevalence; Capability Approach and Nussbaum’s Central Human Capabilities.

Capacidades humanas infantiles y maltrato infantil: un estudio piloto de

una escuela secundaria en Aruba

Resumen: No hay estudios conocidos que hayan explorado una base conceptual para valorizar al maltrato infantil como un impedimento para el desarrollo humano utilizando el Enfoque de Capacidad Humana. El estudio piloto evaluó la prevalencia del maltrato infantil entre 68 (N = 219) niños en edad escolar de 12 a 17 años en una escuela secundaria en Aruba, utilizando la lista de Nussbaum sobre diez capacidades humanas centrales. La prevalencia del maltrato infantil es del 100%. Los tipos de maltrato infantil más frecuentes fueron: el abuso emocional, con 94,2%, abuso físico 88,4%, abuso físico severo 66,7% y negligencia 42%. El abuso sexual tuvo la tasa de frecuencia más baja, en 18,8%. Los niveles de funcionamiento alcanzados variaron según los tipos de maltrato infantil y su prevalencia. La negligencia, presenciar la violencia entre padres y el abuso sexual se asociaron con logros más bajos entre las diez capacidades humanas centrales combinadas, excepto el abuso emocional, el abuso físico y el abuso físico severo que tuvieron la prevalencia más alta. Estos tipos de maltrato infantil eran demasiado altos y dejaban poca o ninguna variabilidad para calcular las relaciones estadísticas con las diez capacidades humanas. Estos hallazgos son preocupantes y generan inquietudes sobre la normalización del abuso. Se recomienda realizar más investigaciones para determinar los factores que contribuyen al uso generalizado del abuso físico y emocional y el potencial de transmisión intergeneracional del maltrato infantil. Se recomienda, además, realizar investigaciones futuras con una muestra más grande que pudiera proporcionar un análisis significativo del espacio de capacidad de los niños afectados por el maltrato infantil.

Palabras clave: Maltrato infantil; prevalencia; frecuencia; enfoque de capacidades y las ‘Capacidades Humanas Centrales’ de Nussbaum.

1. Introduction

Child maltreatment is a human rights, social and public health concern with far-reaching consequences for the child, family, community and across generations. In 2018, UNICEF conducted a quick scan of the child protection system in Aruba and one of the key findings was a lack of data to budget for child protection (Filbri, 2018). A similar conclusion was made in the 2015 Concluding Observations on the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) fourth periodic report of The Netherlands lamenting the lack of data about children in Aruba and recommending the need to expeditiously improve its data collection system (United Nations, 2015, CRC/C/NDL/CO/4). The purpose of this pilot study is to provide estimates of the prevalence of child maltreatment and to determine the likely impact of child maltreatment on human development.

2.State of the art

There already exists a plethora of research that has positioned the adverse effects of child maltreatment from health, psychological and sociological perspectives (Tran et al. 2017; Jemmott, 2013; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016; Roopnarine & Jin 2016 & Kong, 2018). Similarly, there are studies that have found the impact of child maltreatment across the lifespan to have direct economic cost, such as visits to health care providers as well as indirect costs from loss of productivity, disability, decreased quality of life, premature death, the justice system, social service agencies, institutions, places of safety, foster care and adoption (World Health Organization, 2008; Krug et al. 2002; Currie & Widom, 2010; Peterson et al. 2018). However, not much has been researched to theorize child maltreatment within a human development perspective. This paper explores a conceptual basis for valorizing child maltreatment as a human development deprivation or impediment, in which the range of options a child has in deciding what kind of life to lead after the experiences of child maltreatment is adversely compromised. As such, the Human Capability Approach with special reference to Nussbaum’s 10 central human capabilities will for the first time be used as the evaluative framework to explore the relationship between child maltreatment and human development.

3. Theoretical perspective

3.1. Rights-Based Perspective and Human Capability Approach

This study is embedded in a human development perspective characterized by a rights-based perspective and the Capability Approach (CA). These two human development perspectives share an ethos to protect and enhance children’s freedom and well-being and are frameworks used by scholars and practitioners to build strong links between theory and practice (Robeyns, 2017). The CA was pioneered and influenced by Amartya Sen from the disciplines of Economics and Philosophy (1987, 1999) and Martha Nussbaum from Philosophy (2008, 2011). Since then, scholars from multiple disciplines have applied the CA to technology, engineering, environment, innovation, education, psychology, justice, health, poverty, and social policy.

3.2. Why Nussbaum’s Perspective of the Capability Approach?

Nussbaum describes the CA as a method to assess the quality of life of an individual and theorize about basic social justice (2011). The contributions to the CA that qualify Nussbaum as a better evaluative space for this study when compared with Sen are etched on Nussbaum’s principles of vulnerability and cost-effectiveness; openness to applying the CA to children as regards the notion of freedom; recognizing child’s rights as a distinct species of human rights (Nussbaum & Dixon, 2012), and the normative list of 10 central human capabilities designed to bestow dignity to each human life (Nussbaum, 2008 & 2011). The two concepts of functionings and capabilities which Sen and Nussbaum have agreed upon (Nussbaum, 2011; Robeyns, 2003) are also useful for this study. In Robeyn’s (2016) three-fold modular options in the application of the CA, she cautions that any attempt to apply the CA must include capabilities, or functionings or both as part of its basic anatomy. Functionings and capabilities i.e., achievements and opportunities are best defined by Sen (1987): “A functioning is an achievement, whereas a capability is the ability to achieve. Functionings are in a sense, more directly related to living conditions, since they are different aspects of living conditions. Capabilities, in contrast, are notions of freedom, in the positive sense: what real opportunities you have regarding the life you may lead” (p. 36).

3.3. Freedom for Children

Sen does not fully support the application of the CA to children, given his conceptualization of the core concept ‘capability as freedom’, citing that children are not mature enough to make decisions by themselves and will only enjoy their capability when they become adults (Saito, 2003). Sen contends that what matters is not the freedom a child has now, but of the freedom children will have in the future based on the choices made for them by their parents and those in authority (Saito, 2003). In a similar way, Ballet et al. (2011) note that the “CA obviously implies the individual’s capacity for self-determination which may not apply to children” (p. 25). This position is instructive for child maltreatment as it presupposes that those in authority have the skills, knowledge, attitudes, and wisdom to make the right choices in the nurturing of children to secure a flourishing future with opportunities and the freedom to lead lives that they have reason to value. The prevalence of child maltreatment worldwide debunks this view. As such, to subscribe to the notion that children are safe under the omnipotent mantle of persons in authority is to “create a specific image of childhood that ultimately enables adults to colonize children and control their lives” (Burman, 2008 as cited in Peleg, 2013, p. 526), using varied forms of abuse, neglect and exploitation and taking advantage of their vulnerability. Unlike Sen (1999) and Ballet et al. (2011), Nussbaum and Dixon (2012) hold the view that the CA can be used as a theoretical justification for prioritizing children’s welfare rights. Meanwhile, Peleg (2013) asserts: “Reconceptualizing children’s right using the CA can accommodate simultaneously care for the child’s future and the child’s life at the present; promote respect for a child’s agency and active participation in her own growth and lay the foundations for developing concrete measures of implementation” (p. 523).

3.4. Vulnerability and Cost Effectiveness Principles

The vulnerability principle is invoked “where children are especially vulnerable as a result of their legal and economic dependence on adults as well as their inherent physical or emotional vulnerability” (Dixon & Nussbaum, 2012, p. 554). The cost-effectiveness principle is raised “where the marginal cost of protecting children’s rights is either so low that denying such a right would be a direct affront to their dignity, or where it is far more cost-effective to protect that right than an equivalent right for adults” (Dixon & Nussbaum, 2012, p. 554). Both principles can be related to child maltreatment, although not mentioned specifically by Dixon and Nussbaum, but implied.

The CRC is a human rights instrument based on the premise that children are vulnerable and from conception depend wholly on their parents for their psychosocial developmental needs and end up suffering the consequences of their parents’ choices as the ones legally and morally responsible for their care (Matthews, 2019). Moreover, the vulnerability of children is exacerbated by abuse and neglect, either within or outside the family environment. Some children are too young to have the vocabulary to disclose their abusive experiences, yet alone to protect themselves and have the voice to say no, as well as the agency to negotiate their protection from an abuser. Other children may harbour feelings of fear, shame and guilt and a sense of obligation to keep the abuse as a family secret under a false pretence to keeping the family together. Consider child sexual abuse in which children who have less knowledge, maturity and physical strength, can they really protect themselves from sexual predators? The answer is a categorical no as they remain at increased risk of vulnerability of being easy targets to this type of abuse (UNICEF, 2014). Cost effectiveness, lack of public spending for personnel and services (World Vision, Latin America and Caribbean, 2012) and fiscal consolidation and adjustment measures (International Labour Office, 2015) are often lamented to be the principle weakness in the child care and protection systems.

3.5. Nussbaum’s 10 Central Human Capabilities

Nussbaum (2008 & 2011) employs a list of ten central human capabilities that she posits are constitutional guarantees and offer a comprehensive assessment of the quality of life and basic social justice in a society. These are life; bodily health; bodily integrity and safety; senses; imagination and thought; emotions; practical reason; affiliation; other species; play and control over one’s environment (Table 1). Nussbaum states “my claim is that a life that lacks any one of these capabilities, no matter what else it has, will fall short of being a good human life” (Nussbaum, 2011). Child maltreatment represents grueling experiences that can interfere with functional capabilities, and poses the question: what would a good and normal life look like for children who are victims? Nussbaum’s list of 10 core human capabilities can be integrated into a prevalence study on child maltreatment to predict the potential impact of child maltreatment on human development. Table 1 illustrates the definitions of capabilities from Nussbaum’s (2008) theoretical constructs.

Table 1. Measuring the Human Capabilities of Children who Experience Child Maltreatment

10 Central Capabilities

Nussbaum (2008)

Definitions of Central Capabilities,

Nussbaum (2008)

Children’s Capabilities

Adapted from Biggeri & Mehrotra 2011; Biggeri & Libanora, 2011; and Anich et al. 2011

- Life

Being able to live to the end of human life of normal length

Life and physical health

- Bodily health

Health, nutrition, and shelter

Mental health

- Feeling happy

- Inner peace and spirituality

Shelter

- Living in a comfortable/safe home

- Bodily integrity and safety

Move freely from place to place and secured against assault

Mobility

- Moving freely from place to place

- Moving freely and visiting relatives or friends

Freedom from abuse and neglect

- Being free of any form of abuse and discrimination

- Senses, imagination, and thought

Able to use senses, imagine, think and reason

Personal autonomy

- Being able to make sense of the most important things that are happening to me in my life

- Having a say in decisions about myself

Education

- Attending school and doing extracurricular activities

- Emotions

Have attachments with things and people for emotional development

Love and care

- Love and care from my parents

- Love and care from my brother(s) and sister(s)

- Love and care from my teacher(s)

- Love and care from my friend(s)

- Practical reason

Reflect on a plan of life

Personal autonomy

- Being able to plan or imagine my life in the future

- Affiliation

Living for and in relation to others

Social relations

- Participating in activities with my family or neighborhood

Respect

- Receiving respect and consideration from everybody

Religion and identity

- Attending religious celebrations and cultural festivals

- Other species

Living in relation to animals and nature

Environment

- Living in a clean environment

- Play

Laugh, play and recreate

Leisure activities

- Having enough time to play

- Control over one’s environment

Right of speech and political participation

Time autonomy and undertake projects

- Having enough time to do what I really like

- Expressing my personal opinions and ideas and be listened to

It is important to observe that all but one of the 10 central human capabilities (i.e., Other species – living in relation to animals and nature) are reflected in the CRC. Therefore, the entitlements to these capabilities and rights arguably cannot be challenged as they have universal acceptance for the realization of the development of children (Peleg, 2013). Every child is entitled to achieve a certain threshold in all these 10 capabilities and failing to do so constitutes a social injustice (Scbweiger & Gunter, 2015).

Nussbaum’s list of human capabilities has been used to influence the measurement of the capability of children between the ages of 5 and 15 years living in poverty in Afghanistan (Biggeri & Mehrotra, 2011), street children in Kampala, Uganda (Anich et al. 2011) as well as to identify the relevant capabilities that contribute to children’s well-being (Biggeri & Libanora, 2011). Addabbo and Di Tommaso (2011) used two of Nussbaum’s ten capabilities to measure the capabilities of 6 – 13-year-old children in Italy. Comim (2008) applied the CA to evaluate the impact of capabilities on children who pursued a music program in a primary school in Brazil.

4. Methods

4.1. Sample

The pilot survey was conducted in one secondary school in Aruba with a sample of 68 students (N=219) aged 12 – 17 years. Thirty-six percent (36.8%) were male and 61.8% female and one no response as regards to sex. One class was randomly chosen from the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th class to participate in the pilot. 66.2% of the children were from Aruba, 7.4% were from the Netherlands and the Dominican Republic and the remaining children were from Colombia, Venezuela, St. Maarten, Saba and St. Eustatius. Children who resided with both parents represented 41.8%, whilst 35.8% lived with their mothers only. The children in the study had an average of two siblings.

4.2. Definitions of Key Variables

Children refer to persons between the ages of 12 – 17 years old. “Child maltreatment is the abuse and neglect that occurs to children under 18 years of age” (World Health Organization, 2016). The survey focused on eight types of child maltreatment; neglect; emotional abuse; physical abuse; severe physical abuse; witnessing inter-parental violence; sexual abuse; sexual abuse outside the family and sexual abuse within the family. These types of child maltreatment were also used in the National Incidence Study-4 of the United States of America (Sedlak et al. 2010) and The Netherlands’ Prevalence on Maltreatment of Children and Youth (Euser et al. 2013).

Capabilities derive from the Human Capability Approach and refer to what persons or children are able to do and be; and what they value and have reason to value (Sen, 1999). The CA to a child is concerned with his or her actual ability to achieve various valuable functionings, opportunity, and agency as a part of daily living after experiencing various types of child maltreatment. For the purpose of this research, capabilities refer to the ten central human capabilities of Nussbaum, (2008) (Table 1).

4.3 Measures

A self-administered digital Children and Youth Capabilities and Child Maltreatment National School Survey of 137 questions consisting of 7 parts were used. Parts 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 of the survey derived from the NPM 2010 child maltreatment prevalence study in The Netherlands (Euser et al. 2013) which was also conducted in Suriname (van der Kooij, 2017). These parts of the questionnaire originally derived from the Dating Violence Questionnaire (DVA; Douglas and Straus, 2006) and Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales (CTSPC; Straus et al. 1998). There were 18 items about sociodemographic backgrounds of the respondents and their families. As regards the measurement for child maltreatment, there were 35 items and consisted of physical abuse – 8 items; witnessed inter-parental violence - 7 items relating to physical violence between parents; emotional abuse – 4 items; sexual abuse – 8 items, divided between abuse within and outside the family, and neglect consisted of 8 items. Lifetime and year prevalence were measured by asking respondents to rate how many times a certain event had occurred in previous years or in the past 12 months using a 7 point Likert scale (1 = never and 7 more than 20 times); (Table 2). Part 6 consisted of 5 questions about how children coped with unpleasant childhood experiences. Part 7 measured children’s human capabilities and consisted of 2 main items with 18 and 17 sub-items respectively. These questions were adapted from the studies of Biggeri & Mehrotra (2011); Biggeri & Libanora, (2011); Anich et al. (2011).

The survey questions were reviewed by stakeholders from the childcare and protection services sector and by representatives from the Department of Education and the Central Bureau of Statistics to obtain feedback and to ensure the cultural relevance of the survey items. Minor adaptations were made. One such example pertained to the item ‘My bike has been stolen’ that was changed to ‘My cellphone has been stolen’ because bikes are not often used as a form of transportation in Aruba compared to The Netherlands.

Table 2. Child Maltreatment Items

Types of child maltreatment

Items

Emotional abuse

- My mother/father threatened to spank or hit me but did not do so.

- My parents/guardian yelled and screamed at me.

- My parents/guardian has used bad language to me.

- My parents/guardian has called me idiot, stupid or lazy.

Neglect

- My parents/guardian made sure I went to the school when I was a child below 6 years old.

- My parents/guardian made sure I was clean when I was a child below 6 years old.

- My parents/guardian would comfort me when I was upset when I was a child below 6 years old.

- My parents/guardian bought me enough clothes to be comfortable when I was a child below 6 years old.

- My parents/guardian have encouraged me to do my best.

- My parents/guardian helped me when I had problems

- My parents/guardian helped me with my homework.

- It did not matter my parents/guardian if I got into trouble at school.

Physical abuse

- My mother/father has hit me on my bottom with a belt, hairbrush, stick or another hard object.

- My mother/father has hit me with a belt, hairbrush, stick or another hard object

on other parts of my body, besides my bottom.

- My mother/father has grabbed me by the throat and choked me.

- My mother/father has beaten me very hard over and over again.

- My mother/father has wounded me deliberately with a hot or steaming object.

- My mother/father has punched me with their fist or kicked me very hard.

- My mother/father has threatened me with a knife or gun.

- My mother/father has slammed me to the ground or beaten me.

Sexual abuse within the family

- An adult member of my family has had sex with me.

- An adult member of my family has forced me to look at his/her private parts or touched them or him/she looked and touched my private parts.

- A child/youth of my family has forced me to look at or, touch his/ her private parts, or he/she has looked at or touched my private parts.

- A child/youth of my family has done things to me that could be considered as sexual abuse (penetration or oral sex).

Sexual abuse outside the family

- An adult who is not part of my family has had sex with me.

- An adult who is not a member of my family has forced me to look at his/ her private parts or touched them, or he/ she has looked and touched my private parts.

- A child/youth who is not a member of my family has forced me to look at or, touch his/ her private parts, or he/ she has looked at or touched my private parts.

- A child/youth who is not a member of my family has done things to me that could be considered sexual abuse (penetration or oral sex).

Witnessed interparental violence

- My mother/father has forcefully pushed or grabbed or shoved the other.

- My mother/father has slapped the other.

- My mother/father has kicked, bitten or punched the other.

- My mother/father has hit the other with an object or tried to do so.

- My mother/father has beaten up the other.

- My mother/father has threatened the other with a knife or gun.

- My mother/father has used a knife or gun against the over.

4.4. Procedure

The data was collected digitally using Survey Monkey, giving the children a choice to select from four languages; Spanish, English, Papiamento and Dutch. Parental permission letters were issued to students using the passive consent formula, and the assent of the children was also solicited. On the days of data collection, there were at least three School Social Workers and a Mentor inside the computer lab where the children completed the online survey. Another School Social Worker was situated outside the computer lab with the purpose of obtaining feedback from the students about the survey and to provide immediate counseling support if they needed to cope with any distressing thoughts and feelings. The students reported that the survey went well and there was no need to provide counselling support, both during and after the survey period. Each respondent received an information card with a directory of agencies and professionals to contact for support if needed.

4.5. Statistical Analyses

The data was analyzed using SPSS version 24. Prevalence estimates were computed as the proportion of maltreated students of the total number of respondents. Respondents were considered to have experienced child maltreatment if they reported any experience of maltreatment, regardless of frequency. Pearson correlation was conducted to examine the linear relationship between the eight categories of child maltreatment and the 10 human central capabilities. Pearson correlation is used in case of two variables that are both continuous or one variable is continuous and the other variable is dichotomous (Field, 2018; Pallant, 2016; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2018). Pearson correlation produces correlation coefficients, r. If r is .1 to .29, the correlation is weak, .3 to .49, medium, and .5 or greater strong (Cohen, 1988). The various forms of child maltreatment are coded as 0 and 1, where 1 is yes and 0 is no. For human capabilities, low scores represent greater achievement of human capabilities. So, a positive correlation indicates that child maltreatment is associated with lower achievements of human capabilities. The social desirability items were answered completely by all the students. The z scores for the social desirability values ranged from 2.12 and -2.31. These scores were within the -.3.29 and 3.29 z-score range indicating they did not reach statistical significance at the .05 level. Therefore, there were no outlier social desirability scores and as such none of the entries were deleted.

5. Results

5.1. Prevalence of Child Maltreatment

Prevalence was calculated across two time periods; lifetime and the past year. Results indicated both lifetime and year prevalence at 100% (Table 3). Ninety-four percent (94.2%) of children in the pilot reported being emotionally abused over their lifetime and 69.6% in the past year. The lifetime prevalence of physical abuse among children was 88.4% and 36.2% in the past year, which indicates that physical abuse rates are not nearly as high in year prevalence as they are across the children’s lifetime. The lifetime prevalence for severe physical abuse was 66.7%, and for the past year was only 18.8%. Of all child maltreatment, the various forms of sexual abuse had the lowest prevalence rates which ranged from a lifetime prevalence of 18.8% to 2.9%-year prevalence of sexual abuse within the family (Table 3).

Table 3. Child Maltreatment Prevalence

Lifetime

Past Year

Neglect

42%

*

Emotional abuse

94.2%

69.6%

Physical abuse

88.4%

36.2%

Physical abuse severe

66.7%

18.8%

Inter-parental violence

34.8%

8.7%

Sexual abuse

18.8%

10.6%

Sexual abuse outside family

13.0%

8.7%

Sexual abuse within the family

Total

10.1%

100%

2.9%

100%

*Neglect only measured lifetime experiences

5.2. Child Maltreatment Prevalence by Gender

The findings revealed that there were no differences in the experiences of boys and girls with lifetime prevalence of emotional abuse (96.0% vs 95.2%); physical abuse (96.0% vs 95.2%); severe physical abuse (76.0% vs 61.9%); witnessing interparental violence (40% vs 35%) and sexual abuse in general (20.8% vs 19.5%). However, for year prevalence more boys were at risk of sexual abuse in general (20.8% vs 4.9%). The results also indicated that for both lifetime and year prevalence, there were differences in the experiences of sexual abuse outside the family between gender, where boys were at higher risk than girls (20.8% vs 9.8% L; and (20.8% vs 2.4% Y). Meanwhile, girls were likely to experience more sexual abuse within the family than boys over a lifetime as well as during the past year (Table 4).

Table 4. Child Maltreatment Prevalence by Gender

Lifetime (L) (n=68)

Year (Y) (n=68)

Boys

n=25

Girls

n=42

Overall

n=68

Boys

n=25

Girls

n=42

Overall

n=68

Neglect

28.0%

53.7%

42%

Emotional abuse

96.0%

95.2%

94.2%

60.0%

76.2%

69.6%

Physical abuse

96.0%

87.8%

88.4%

33.3%

40.0%

36.2%

Physical abuse severe

76.0%

61.9%

66.7%

25.0%

16.7%

18.8%

Inter-parental violence

40.0%

35.0%

34.8%

8.0%

10.3%

8.7%

Sexual abuse

20.8%

19.5%

18.85

20.8%

4.9%

10.6%

Sexual abuse outside family

Sexual abuse

within family

20.8%

4.0%

9.8%

14.3%

13.0%

10.1%

20.8%

0.0%

2.4%

4.8%

8.7%

2.9%

TOTAL*

100.0%

100%

100%

100%

100%

100.0%

* Denotes the percentage of children who experienced at least one form of child maltreatment

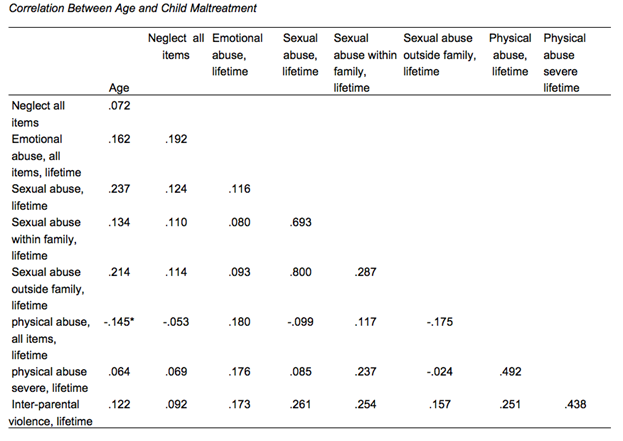

To assess the relationship between age and types of child maltreatment, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted. Pearson correlation analysis can be used when one variable is continuous and the other variable is a dummy coded dichotomous variable (Field, 2018; Pallant, 2016; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2018). The results indicated that there was a significant negative relationship between age and physical abuse (r = -.145, n= 68, p < .05), where decreases in age were associated with greater prevalence of physical abuse. However, there was no significant linear relationship between age neglect (r = .072, n= 68, p > .05), emotional abuse (r = .162, n = 68, p > .05), sexual abuse (r = .237, n = 68, p < .05), sexual abuse within the family (r = .134, n = 68, p < .05), sexual abuse outside the family (r = .214, n = 68, p < .05), severe physical abuse (r = .064, n = 68, p >.05), and inter-parental violence (r = .122, n= 68, p > .05). See Table 5.

Table 5

* - significant at the .05 level ** - Significant at the .01 level

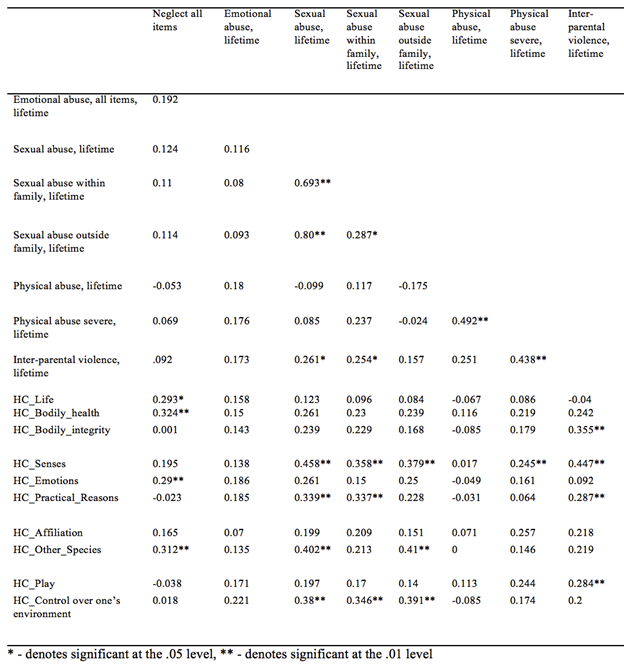

5.3. Child Maltreatment and the 10 Central Human Capabilities

To measure the level of achieved functionings of children, they were given a list of identified capabilities to indicate to what extent they enjoyed them in their lives as ‘completely’, ‘insufficiently’, ‘sufficiently’ or ‘not at all’. A Pearson correlation was performed to assess the relationship between child maltreatment and each of the 10 human capabilities. There was no statistically significant relationship between emotional abuse and physical abuse with any of the 10 human capabilities (Table 6 & Figure 1). However, severe physical abuse was significantly positively related to the human capability ‘senses, imagination and thought’ r = .245, n = 68, p < .01. This translates to children’s deprived capability of making sense of the most important things that are happening in their lives; not having a say in decisions about themselves and inability to attend extra-curricular activities after school.

The results indicated that there was a significant positive correlation between neglect and the ‘life’ human capability, r = .293, n=68, p < .05, meaning that neglect was associated with children’s deprived capability to live a normal length of life. Neglect was also statistically correlated with the ‘bodily health’ human capability, r = 324, n = 68, p< .01, indicating that neglect was associated with children’s health, nutrition, and shelter. The correlation also revealed that neglect was associated with poorer ‘emotions’ i.e., love and care from parents, siblings, teachers and friends (r = .290, n = 68, p < .01) and greater difficulties with ‘other species’, i.e., living in relation to animals and nature r = .312, n = 68, p <.01.

Child maltreatment has three forms of sexual abuse, sexual abuse overall, sexual abuse within the family, and sexual abuse outside of family. The results of the Pearson correlation indicated that there was a statistically significant relationship between the ‘senses, imagination and thought’ human capabilities and sexual abuse overall (r=.458, n = 68, p< .01); sexual abuse within family (r = .358, n = 68, p<.01); and sexual abuse outside of family, r = .379, n = 68, p <.01. Human capabilities of ‘Control over one's environment’ was also significant related to sexual abuse overall (r = .380, n = 68, p <.01), sexual abuse within family (r = .346, n = 68, p < .01), and sexual abuse outside of family, r = .391, n = 68, p <.01. These results indicated that the three types of sexual abuse were associated with children’s lower capability achievements to make sense of the most important things that are happening to them in their lives; not having a say in decisions about themselves and inability to attend extra- curricular activities after school (Table 6 & Figure 1).

Sexual abuse overall (r = .339, n = 68, p<.01), and sexual abuse within family (r = .337, n = 68, p = <.01) were significantly positively related to the human capability ‘practical reason’ which means that these children were more likely to be deprived of the capability to plan or imagine their lives in the future. Overall sexual abuse (r = .402, n = 68, p < .01) and sexual abuse outside of family (r = .410, n = 68, p <.01) were significantly positively related to ‘other species’. This means that children who experience these types of sexual abuse had greater difficulties living in relation to animals and nature (Table 6 & Figure 1).

Finally, inter-parental violence was significantly positively related to ‘bodily integrity and safety’ (r = .355, n = 68, p < .01), ‘senses, imagination and thought’ (r = .447, n = 68, p < .01), ‘practical reasons’ (r = .287, n = 68, p < .01), and ‘play’, r = .284, n = 68, p < .01). The results indicated that children who witness inter-personal violence was associated with poorer capabilities to move freely from place to place and secured against assault; being able to make sense of the most important things that are happening to them in their lives; having a say in decision about themselves; being able to plan or imagine their lives in the future as well as the ability to laugh, play and recreate (Table 6 & Figure 1).

Table 6. Relationship Between Child Maltreatment and Human Capabilities

Figure 1. Relationship Between Child Maltreatment and the 10 Human Capabilities

5.4. Relationship Between Child Maltreatment and the Combined 10 Human Capabilities

As regards the relationship between all forms of child maltreatment and the combined 10 human capabilities, a mean composite score was computed using all 10 human capabilities. Results of the Pearson correlation between the forms of child maltreatment and the composite score for human capabilities indicated that five of the eight types of child maltreatment had a significant positive relationship. First, there was a significant positive relationship between neglect and total human capabilities (r = .253, n = 68, p< .01), indicating that neglect was associated with lower achievements of the total human capabilities. Second, there was a significant positive relationship between sexual abuse (r=.403, n = 68, p<.01), sexual abuse within family (r = .325, n = 68, p<.05) and sexual abuse outside of family, r = .345, n = 68, p<.05, and total human capabilities. The results indicate that overall sexual abuse, sexual abuse within family, and sexual abuse outside of family were associated with lower achievements of the total human capabilities. Finally, inter-parental violence was significantly related to total human capabilities, r = .338, n = 68, p<.01) (Table 7 & Figure 2).

Table 7. The Relationship between Child Maltreatment and Combined 10 Human Capabilities

Neglect all items

Emotional abuse, lifetime

Sexual abuse, lifetime

Sexual abuse within family, lifetime

Sexual abuse outside family, lifetime

Physical abuse, lifetime

Physical abuse lifetime

Inter-parental violence, lifetime

Neglect

prevalence

Neglect all items

Emotional abuse, all items, lifetime

.192

Sexual abuse, lifetime

.124

.116

Sexual abuse within family, lifetime

.110

.080

.693**

Sexual abuse outside family, lifetime

.114

.093

.800**

.287*

Physical abuse, all items, Lifetime

-.053

.180

-.099

.117

-.175

Physical abuse severe, lifetime

.069

.176

.085

.237

-.024

.492

Inter-parental violence, lifetime

.092

.173

.261

.254

.157

.251

.438

HC Total

.253*

.204

.403**

.325*

.345*

.011

.265

.338**

* - denotes significant at the .05 level, ** - denotes significant at the .01 level

Figure 2. Relationship BetweenChild

6. Discussion

6.1 Prevalence of Child Maltreatment

The prevalence of child maltreatment in the studied sample was 100% (n=68) compared with 33.8%% (n=1,920) in The Netherlands (Euser et al. 2013) and 86.3% (n=1,311) in Suriname (van der Kooij, 2017). These are comparable studies from countries that share a similar socio geopolitical history with Aruba, keeping in mind that their sample sizes were much greater. Emotional abuse was the most common type of child maltreatment experienced by the studied sample at a rate of 94.2% compared with The Netherlands, 8.5% (Euser et al. 2013) and 53.1% (van der Kooij, 2017) in Suriname. Physical abuse as the second highest type of child maltreatment is considered high at 88.4% when compared with 53.4 % in Suriname (van der Kooij, 2017) and 7.2 % in The Netherlands (Euser et al. 2013). Meanwhile, the year prevalence for emotional and physical abuse was 69.9% and 36.2% respectively. This indicated that physical abuse prevalence rates are not nearly as high in the past year as they were across the children’s lifetime. This is consistent with studies that have shown that younger children are beaten more than adolescents (Gershoff, 2002). Of all the types of child maltreatment, sexual abuse had the lowest prevalence rates of 18.8% lifetime prevalence. There were similar findings in Suriname where the prevalence rate of child sexual abuse is at 20.7% (van der Kooij, 2017). However, when compared with The Netherlands, the prevalence rate of child sexual abuse was much lower than Aruba at 2.2% (Euser et al. 2013).

6.2. Child Maltreatment and Human Capabilities

There appears to be some difficulty in interpreting the results given the high prevalence of child maltreatment in the study. Nonetheless, the findings show a positive linear correlation among six of the eight types of child maltreatment with the separate10 human capabilities which are neglect, severe physical abuse, child witness to inter-parental, sexual abuse in general and sexual abuse within and outside the family. There was also a positive linear correlation among five of the eight types of child maltreatment with the combined 10 human capabilities. Physical and emotional abuse which had the highest prevalence rates were not associated with any of the separate 10 human capabilities as well as the combined 10 human capabilities. This might be because there were not enough respondents who had not reported these types of child maltreatment to calculate statistically the relationships between human capabilities and child maltreatment.

In search for further explanations, it may be possible to consider the results as being consistent with the normalization of abuse as studies have shown that children who grow up in abusive home environments and are not protected, accept the abuse as normal because they somehow become convinced that they deserved to be treated in that manner and grow up to acknowledge it as part of their life (Wert et al. 2019; Wilson, 2016, Pears & Capaldi, 2001). It is also possible that the normalization of physical and emotional abuse is associated with these practices as common in Caribbean cultures (Jin, et al. 2016; Barrow & Ince, 2008). Moreover, the Criminal Code of Aruba makes provisions for ‘educative smacking and slapping’ (CRC/C/N/D/4, 2014, p. 120) which may make it difficult for parents to know when, where and how to draw the line. This has implications for perpetuating a multigenerational transmission process of abuse and must be taken seriously for action.

It may also be possible to consider the notion of resiliency on the part of the children, because while there is a preponderance of research that associates child maltreatment with adverse emotional and behavioral outcomes across lifespan, there remains a body of research that asserts variability of its effects that render some children resilient (Afifi & MacMillan, 2011; Edwards et al. 2014). A stable family environment and supportive relationships are identified as family-level factors and personality traits as individual-level factors for the child (Afifi & MacMillan, 2011). In our case, it may also be probable to infer that the children are ingeniously finding supporting adult relationships and taking a more optimistic stance on their view of their lives. Or, like Baumrind (2012) asserted, within a normative culture of abuse, children are likely to have accepted abuse as parental care and concern.

The findings show a variation in the level of functionings achieved according to the child’s experiences with maltreatment. Children in the pilot who experienced neglect, for example, reported not having achieved the central capability dimensions of ‘life’; ‘bodily health’; ‘emotions’; and ‘other species’. These deprivations are characterized by not being able to live to the end of human life or normal length; not feeling happy and experiencing inner peace and spirituality and living in a comfortable/safe home. It also refers to not having attachments with things and people for their emotional development especially from parents, siblings, teachers, and friends. On the other hand, those children who experienced sexual abuse reported more likely to be deprived from the capabilities of ‘senses, imagination and thought’, ‘practical reasoning’ as well as ‘other species’. This translates to deprivation from personal autonomy, inability to make sense of the most important things that are happening in their lives and having a say in decisions about themselves; an inability to plan, or imagine their life in the future as well as living in relation to animals, nature and in a clean environment. Finally, children who witnessed inter-parental violence reported being capability deprived in the dimensions of ‘bodily integrity and safety’; ‘practical reason’ and ‘play’.

Rethinking child maltreatment and its impact on children’s development and well-being from a CA opens a new perspective for research. It is expected that the national school survey with a much larger sample may provide greater opportunities for more meaningful analysis of the capability space of children affected by child maltreatment.

6.3 Limitation and strengths

The study provides the best available knowledge about the scope of child maltreatment for only one school in Aruba but its findings cannot be generalized. It should serve as baseline data and a catalyst for action to better protect the children who attend the school towards ensuring that they live long, healthy and creative lives of flourishing and well-being. In exploring the relationship of child maltreatment with human capabilities, it did not control for resilience. The study included children between the ages of 12 - 17 years and the findings may not represent the experiences of younger age children. Another possible limitation is the inability to authenticate the list of children’s capability set given the fact that the children were given a predetermined list with no opportunity to produce their own knowledge of functionings and capabilities in their own lives. One possible way to circumvent this limitation is to complement future research with a qualitative design with both younger children and adolescents, thereby making them active participants in the research process and derive a legitimate full set of capabilities attuned with their experiences of child maltreatment.

The self-report nature of the survey produced reports of child maltreatment that would not typically come to the attention of the police and child protection services. Moreover, since at the time of the pilot, there were no laws for mandatory reporting of child maltreatment, the findings of the pilot study is a close estimation of the prevalence deriving from self-report of children. The survey was tested for social desirability bias and the results show that there were no outliers.

The survey undoubtedly contributes to the gap in empirical research about the scope of child maltreatment in Aruba, albeit in one school. It is believed that the survey would have raised the awareness of the children about the many dimensions of capabilities in which their lives could be affected by child maltreatment. The final strength is that the research is the first attempt in the Caribbean region to conceptualize child maltreatment using a human development perspective with special reference to the CA and Nussbaum’ list of 10 central human capabilities.

7. Conclusion

The prevalence of child maltreatment in the studied sample is high. Emotional abuse, physical abuse and severe physical abuse were the most prevalent types of child maltreatment experienced by the children in the school. Sexual abuse had the lowest prevalence rate with both boys and girls at equal risk. However, boys are at a much higher risk than girls to experiencing sexual abuse outside the family, whereas girls are at higher risk inside the family. The study also concludes that the level of functionings achieved vary according to the type of child maltreatment and the magnitude of prevalence. In that, neglect, inter-parental violence, sexual abuse outside and within the family were associated with lower achievements of the combined 10 central human capabilities except for emotional abuse, physical abuse, and severe physical abuse. It is therefore concluded that children who experienced the five types of child maltreatment may not be enjoying the minimum threshold required for well-being and flourishing and leading lives that they have reason to value. The non-association among the top two types of child maltreatment with the highest prevalence, i.e., emotional abuse and physical abuse were too common to calculate statistically the relationships with the 10 human capabilities as there was no variability to discern associations.

Given the absence of empirical research to measure child maltreatment using a Human Capability Approach, it is recommended that this relationship be further explored with larger samples and in other cultures and to control for resilience. Considering the widespread prevalence of child maltreatment, especially emotional and physical abuse in the studied sample, an effective and sustained intervention and prevention school and community-based program is required. This must include the dynamic participation of the children, their parents and their families as main actors and beneficiaries.

References

Addabbo, T. & Di Tommaso, M. L. (2011). Children’s capabilities and famiy characteristics in Italy: Measuring imagination and play. In M. Biggeri, J. Ballet & F. Comim (Eds.), Children and the Capability Approach (222-242). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Afifi, T. & MacMillan, H. L. (2011). Resilience following child maltreatment: A review of protective factors. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(5), 266 -272.

Anich, R., Biggeri, M., Libanora, R., & Mariani, S. (2011). Street children in Kampala and NGO’s Action: Understanding capabilities deprivation and expansion. In M. Biggeri, J. Ballet & F. Comim (Eds.), Children and the Capability Approach (107-136). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ballet, J., Bigeri, M. & Comim, F. (2011). Children’s agency and the capability approach: A Conceptual Framework. In M. Biggeri, J. Ballet & F. Comim (Eds.), Children and the Capability Approach (22-45). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Barrow, C. & Ince, M. (2008). Early childhood in the Caribbean. Working papers 47. The Hague, The Netherlands, Bernand van Leer Foundation.

Baumrind. D. (2012). Differentiating between confrontive and coercive kinds of parental power-assertive disciplinary practices. Human Development, 55(2), 35- 51. https://doi.org/10.1159/000337962

Bigerri, M. & Libanora, R. (2011). From valuing to evaluating: Tools and procedures to operationalize the capability approach. In M. Biggeri, J. Ballet & F. Comim (Eds.), Children and the Capability Approach (79-106). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bigerri, M. & Mehrotra, S. (2011). Child poverty as capability deprivation: How to choose domains of child well-being and poverty. In M. Biggeri, J. Ballet & F. Comim (Eds.), Children and the Capability Approach (46-75). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd Ed.). Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Comim, F. (2008). Assessing children's capabilities: Operationalizing metrics for evaluating music programs with poor children in Brazilian primary schools. In R. Gotoh & P. Dumouchel (Eds.), Against Injustice: The New Economics of Amartya Sen (pp. 252-274). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511657443

Currie, J & Widom, C. S. (2010). Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child maltreatment, 15(2), 111-120. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559509355316

Douglas, E. M. & Straus, M. A. (2006). Assault and injury of dating partners by university students in 19 countries and its relation to corporal punishment experienced as a child. European Journal of Criminology, 3, 293-318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370806065584.

Edwards, K, M., Probst, D. R., Rodenhizer, K, A., Gidycz, C. A. & Tansll, E. C. (2014). Multiplicity of Child Maltreatment and Biopsychosocial Outcomes in Young Adulthood: The Moderating Role of Resiliency Characteristics Among Female Survivors. Child maltreatment, 19(3-4),188-198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559514543354

Euser, S., Alink, L. R. A., Pannebakke, F., Vogels, T., Bakermas-Kranenburg, M. J. & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2013). The Prevalence of child maltreatment in the Netherlands across a 5-year period. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(10), 841- 851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.07.004

Field, A. (2018). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (5th Ed.). London: SAGE.

Filbri, M. (2018). Summary Report Quick Assessment Child Protection System Aruba. UNICEF.

Gershoff, E. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull, 128(4), 539-79.

Gershoff, E. T. & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2016). Spanking and child outcomes: old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000191

Jemmott, E. T. (2013) Using our brain: Understanding the effects of child sexual abuse. In A. D. Jones (Ed.), Understanding Child Sexual Abuse Perspectives from the Caribbean (76 -93). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kong. J. (2018). Childhood maltreatment and psychological well-being in later life: the mediating effect of contemporary relationships with the abusive parent. Journal of Gerontology, 73(5), e39-e48. Doi:110/1093/geronb/gbx039.

Krug, E. G., Mercy J. A., Dahlberg, L. & Zwi, A. (2002). The world report on violence and health. The Lancet, 360(9339), 1083-1088.

Matthew, B. (2019). New International Frontiers in child Sexual Abuse: Theory, problems and progress. USA: Springer.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2008). Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Nussbaum, M. C. & Dixon. R. (2012). Children’s rights and a capabilities approach: A Question of Special Priority. University of Chicago Law School. Retrieved from: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1056&context=public_law_and_legal_theory

Pallant, J. (2016). SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS. (6th edn.). London: McGraw-Hill Education.

Pears, K. & Capaldi, D. (2001). Intergenerational transmission of abuse: A two generational prospective study of an at-risk sample. Child Abuse Neglect, 25(11), 1439 -1461.

Peleg, N. (2013). Reconceptualizing the child’s right to development: Child and the capability approach. International Journal of Children’s Rights, 21(3) 523 - 543.

Peterson, C., Florence, C. & Klevens, J. (2018). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States, 2015. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 178-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.09.018

Robeyns, I. (2003). The Capability Approach: An interdisciplinary Introduction. Retrieved from https://commonweb.unifr.ch/artsdean/pub/gestens/f/as/files/4760/24995_105422.pdf.

Robeyns, I. (2016). The Capability Approach. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/capability-approach/

Robeyns, I. (2017). Well-being, Freedom and Social Justice: The Capability Approach Re-Examined. UK: Open Book Publishers.

Roopnarine, J. L., & Jin, B. (2016). Family socialization practices and childhood development in Caribbean cultural communities. In J. L. Roopnarine & D. Chadee, (Eds.), Caribbean Psychology Indigenous Contributions to a Global Discipline (71-96). Washington, D.C: American Psychology Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14753-000.

Saito, M. (2003). Amartya Sen’s capability approach to education: A critical exploration. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 37(1), 17-33.

Scbweiger, G. & Gunter, G. (2015). Social justice for children – A capability approach. A. philosophical examination of social justice and child poverty. In G. Schweiger & G. Gunter. A Philosophical Examination of Social Justice and Child Poverty (pp. 15-66). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sedlak, A. J., Mettenburg, J., Basena, M., Petta, I., McPherson, K., Greene, A. & Spencer, Li. (2010). Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and neglect (NIS-4) Report to Congress. US Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families, Washington, DC. USA.

Sen, A. (1987). The standard of living: lecture II, Lives and Capabilities. Cambridge: University Press, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511570742.003

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Moore, D. W. & Runyan D. (1988). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development ad psychometric data from a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(4), 249- 270. Doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00174-9

Tabachnick, B.G. & Fidell, L.S. (2018). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). USA: Pearson Education.

Tran, N. K., Van Berkel, S.R., van Ijzendoorn, M. H. & Alink, L, R. (2017). The association between child maltreatment and emotional, cognitive and physical health functioning in Vietnam. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 332. Doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4258-z.

Van der Kooij, W. I. (2017). Child Abuse and Neglect in Suriname. Proefschriftmaken. nl.

Wert, M. V., Anreiter, I., Fallo, B. A. & Sokolowski, M. B. (2019). Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: A Transdisciplinary analysis. Gender and the genome, 3, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/2470289719826101

Wilson, D. (2016). Transforming the normalization and intergenerational Whanau (family)

violence. Journal of Indigenous wellbeing Te Mauri- Prmatisiwin, 1(2), 32-43. Retrieved from http://manage.journalindigenouswellbeing.com/index.php/joiw/article/viewFile/49/41

Documents

International Labour Office (2015). Social Protection Policy Papers. Social Protection for Children: Key policy trends and statistics. Paper 14. Social Protection Department. Retrieved from https://www.social-protection.org/gimi/RessourcePDF.action?ressource.ressourceId=51578.

UNICEF (2014). Hidden in plain sight: A Statistical analysis of violence against children. New York. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Hidden_in_plain_sight_statistical_analysis_Summary_EN_2_Sept_2014.pdf.

United Nations (8 June, 2015). Committee on the Rights of the Child. Concluding Observations to fourth period report of The Netherlands. CRC/C/NDL/CO/4.

World Health Organization (2008). Manual for estimating the economic costs of injuries due to interpersonal and self- directed violence. Geneva. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43837/9789241596367_eng.pdf?sequence=1

World Health Organization (2016). Child maltreatment. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment.

World Vision (2012). Latin America and Caribbean, Child Protection Systems in Latin America and the Caribbean: A National and Community Level Study Across 10 countries. Retrieved from https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/LAC_ADAPT_Publication-January_2014_0.pdf.

1. PhD candidate, Masters of Social Worker, Bachelor of Science Degree in Social Work and Bachelor of Arts Degree in Missionary Catechesis. Lecturer, Department of Social Work and Development, Faculty of Arts and Science, University of Aruba. Email: clementia.eugene@ua.aw

2. Professor in Child and Youth Clinical Psychology at the Institute for Graduate Studies and Research of the Anton de Kom University of Suriname. He has over 40 years of experience working in mental health, clinical psychology and psychoanalysis and was trained in the Netherlands. He is an editorial board member of the Caribbean Journal of Psychology. His research and clinical interests are suicide prevention and prevention of violence against children. Email: tobigraafsma@sr.net